In a fitting twist of fate, Israel’s modern wine industry may have finally found its signature identity… in Palestinian territory.

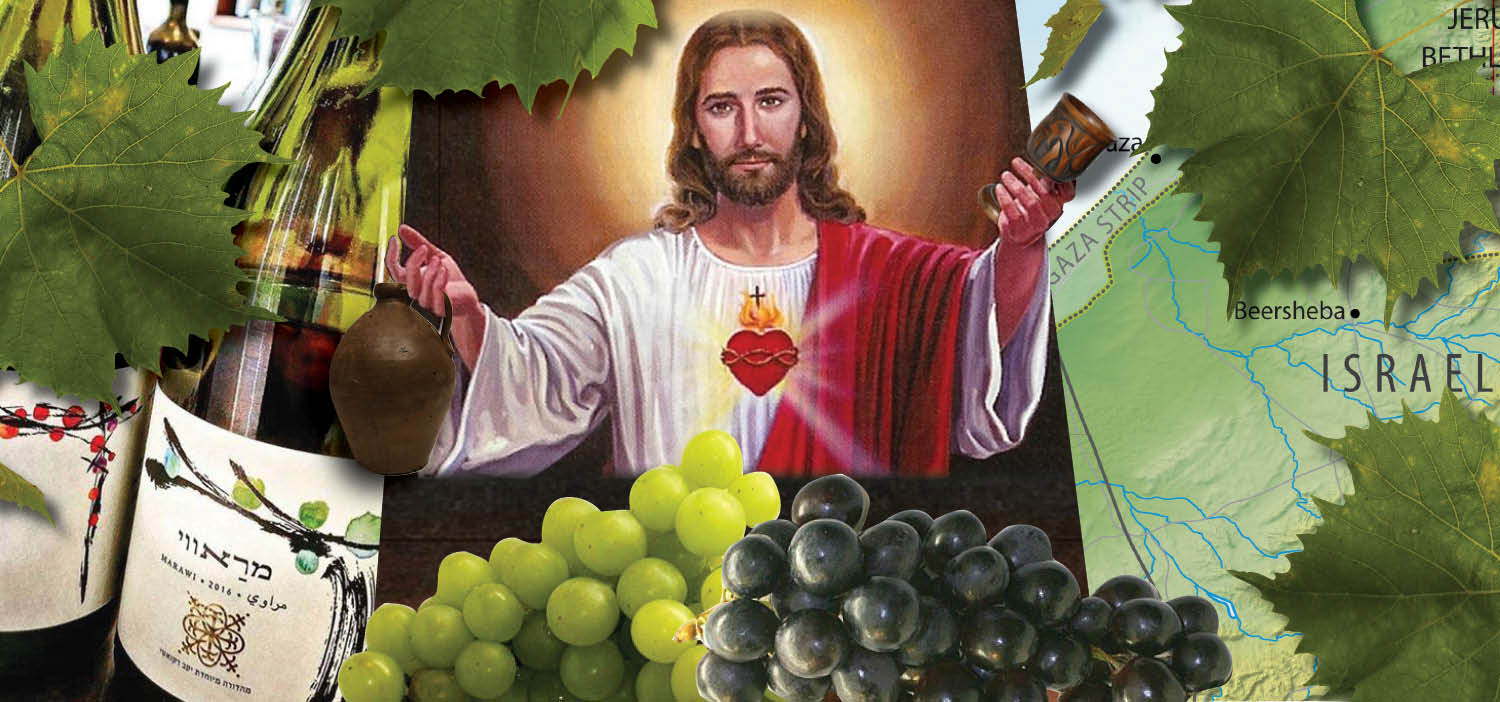

There's an indigenous grape revival underway in the Holy Land, and a handful of ancient varieties are now responsible for some of Israel’s most exciting new wines. The small but growing number of vintners producing wines from these rediscovered grapes means it’s possible to drink the same wines that King David and (yup) Jesus were imbibing over 2,000 years ago.

The awakening began less than a decade ago when winemaker/oenologist Dr. Elyashiv Drori noticed unusual looking grapevines growing wild near his home in a West Bank Jewish settlement.  In partnership with Ariel University, Drori combed the region for forgotten vines and has identified well over one hundred indigenous varieties—both grown wild and cultivated on Palestinian farms (for eating)—which are totally unique from any other grape on earth.

In partnership with Ariel University, Drori combed the region for forgotten vines and has identified well over one hundred indigenous varieties—both grown wild and cultivated on Palestinian farms (for eating)—which are totally unique from any other grape on earth.

(Photo Cremisan vineyards)

To establish their provenance, Drori’s team matched each vine’s plant DNA to grape remains from archeological sites near Jewish temples (primarily found in donkey poop, since animals were fed spent grape seeds and skins after wine fermentation). He also cites evidence in passages in the Babylonian Talmud which reference “Jindali” and “Hamdani” wines as far back as 220 A.D., two of the grapes that he has found.

“In the Holy Land, we just may have the most interesting wine legacy on earth,” says Drori. “We are currently still assessing the various grapes for their ability to make good wine, but we can already say that about 20 varieties show potential.”

Recanati, a well-known mid-size winery in Central Israel’s Hefer Valley, was an early believer. “We tasted dozens of the samples from the research project and were most impressed with the Marawi grape (aka Hamdani),” explains winemaker Gil Shatsberg.

Recanati was the first to release a commercial bottling of Marawi in 2014, with grapes sourced from a Palestinian grower near Hebron in the West Bank. “It’s an aromatic wine, with loads of ripe melon, pear and floral notes and terrific acidity; the texture is surprisingly rich and full, similar to Chenin Blanc or Chardonnay,” Shatsberg describes. Having just released the third vintage, Shatsberg has a greater understanding of how to coax the best from the grape. “It’s amazing to say we produce the finest example of Marawi on the planet,” he half-jokingly proclaims.

More recently, Recanati began working with Bittuni—“Israel’s answer to Pinot Noir,” says Shatsberg—and just unveiled the debut 2016 vintage. With both varieties, Shatsberg noticed almost immediately how unusually suited the vines were to their environment: “They are resistant to mildew and can be dry-farmed with no irrigation, unlike the imported grapes Chardonnay and Cabernet, which are more commonly planted in Israel.” Which is no coincidence, he adds, considering they have survived in the Holy Land for 2,000 years.

More recently, Recanati began working with Bittuni—“Israel’s answer to Pinot Noir,” says Shatsberg—and just unveiled the debut 2016 vintage. With both varieties, Shatsberg noticed almost immediately how unusually suited the vines were to their environment: “They are resistant to mildew and can be dry-farmed with no irrigation, unlike the imported grapes Chardonnay and Cabernet, which are more commonly planted in Israel.” Which is no coincidence, he adds, considering they have survived in the Holy Land for 2,000 years.

For this reason, many believe native vines are better transmitters of terroir, that intangible combination of characteristics that lets a wine express its place of origin. “It may sound strange, but in these wines I can taste the dust that blows from Syria,” says Shatsberg. “I believe that these grapes will allow us to really define what Israeli typicity is.”

The Question of Origin & Ownership

The Holy Land’s ancient wine tradition came to an abrupt halt in the 7th century when Muslims conquered the region and outlawed alcohol. Baron Edmond de Rothschild, a committed Zionist, helped restart winemaking here in the late 19th century, and did so with plantings from his family’s Bordeaux estate, Chateau Lafite, which is why Cabernet, Merlot and Chardonnay are the most planted grapes in Israel.

While these grapes can be crafted into excellent wines, they are relatively recent imports. “We see ourselves as a link in a long chain of winemaking in the Holy Land, disconnected temporarily for 1,300 years by Muslim religious prohibition of winemaking,” says Drori. “The Israeli wine industry needs its story which needs to connect to our very ancient wine history represented in the Bible—these native grapes are a very powerful anchor.”

In addition to breathing new life into Israel’s wine industry, Shatsberg believes the native grapes can, in some small way, provide a bridge between two people in this geo-politically fraught land.  Recanati buys grapes from a Palestinean Muslim grower with five acres of Marawi grapes in a fertile area in the Judean Hills, south of Jerusalem. The grower insists on anonymity—alcohol is forbidden in his community, and working with Israeli’s is frowned upon. “We paid him three times what he had been selling his fruit for,” says Shatsberg. “We’ve become friends; he trusts us now and let’s us come into his vineyard and consult with him. It gives us a way to cooperate with Palestinians.”

Recanati buys grapes from a Palestinean Muslim grower with five acres of Marawi grapes in a fertile area in the Judean Hills, south of Jerusalem. The grower insists on anonymity—alcohol is forbidden in his community, and working with Israeli’s is frowned upon. “We paid him three times what he had been selling his fruit for,” says Shatsberg. “We’ve become friends; he trusts us now and let’s us come into his vineyard and consult with him. It gives us a way to cooperate with Palestinians.”

(Photo Recanati's Marawi Vineyard)

Recanati uses both Arabic and Hebrew on their wines’ labels, and hired an Arab-Israeli singer to perform at the launch party. “We see the native grapes as neither Israeli or Palestinian, but part of the history and ancestry of the Holy Land that belongs to us all.”

By contrast, Drori, who owns a boutique winery in the West Bank settlement of Shiloh, believes the native grapes further establish the Jewish people’s roots and rightful claim to their ancestral land: “Native vines were found throughout Israel and the West Bank. Our connection to the land does not, in my opinion, need strengthening. Nevertheless, our work helps revive the magnificent wine industry which was a major part of daily life for our ancestors in the Holy Land.”

Who lays claim to this land isn’t simply a Jewish-Muslim question. An early pioneer of native grapes is the Cremisan Winery, a Salesian Monastery run by Italian monks and Palestinians in the West Bank near Bethlehem. Located in a rural, mountainous setting somewhat hidden away in the forest amidst olive trees and gardens, Cremisan has been producing wine since 1885—and has been working with indigenous vines since before the Ariel University project.

Winemaker Fadi Batarseh partnered with famous Italian winemaker Riccardo Cotarella to create the Star of Bethlehem wines, based on native grapes Hamdani and Jandali in 2008. The project’s focus, says Batarseh, is on “the idea of origin.” Batarseh also works with Dabouki, an ancient grape that never really went away, having been used for hundreds of years to make Arak, a local distilled spirit; some Dabouki vines are over 60 years old, and Batarseh uses the variety to make a serious white wine.

(Photo Recanati bush vines)

“Cremisan makes wines from international grapes, but I only import their native varietal wines,” says Jason Bajalia, the winery’s U.S. importer (and of Palestinian descent). “These grapes convey so much more sense of place, and I believe they are the future for the region.” As for their origin, Bajalia is unambiguous: “These are Palestinian grapes grown on Palestinean vineyards.”

Producers are unavoidably caught in the cross hairs of larger territorial disputes. For 9 years, Israel tried to construct a wall through the Cremisan Valley—which connects Bethlehem to Jerusalem—in the name of security, which would have cut off many of the Cremisan Winery’s growers from their land. The Vatican interceded on the Christian Palestinians’ behalf and the Supreme Court eventually blocked it.

Drori’s Gvaot winery in the Shiloh settlement is deep within the West Bank and would most certainly be evacuated if there were any land swap between Israel and Palestine in a two state solution. He remains steadfast: “When I first planted olive trees here 20 years ago, people questioned my decision, saying our days in the region were ending. Today my trees are 8 meters high and my 6 children were born and raised here. I’m not one for future fears but present efforts.”

Those present efforts include Gvaot’s just-released limited edition of Jandali—a round, complex wine with white fruit and mineral flavors which Jancis Robinson recently praised.

While a number of other Israeli wineries are replanting their own vineyards with vine cuttings of native grapes, rather than rely solely on Palestinian vineyard sources (Recanati now cultivates acres of Marawi on their estate vineyards; 2019 will be their first vintage), Drori prefers the West Bank’s distinctive terroir. “The West Bank is the most ideal area for grape growing—rocky soils, high-altitude sites, cold nights and warm days—the perfect conditions for complex wine,” he affirms.

The question of origin cuts both ways: There are people who boycott wines grown in Israeli West Bank settlements for political reasons. He insists there are a greater number of people who purchase his wines exactly because of where they are from. “These grapes have finally put Israel on the wine map as a unique terroir with its own varieties and traditions; I believe they are our future.”

Read more from Kristen Bieler on Grape Collective.

Banner art collage by Piers Parlett