If it’s true that the authentic you is reflected in what you do, then Jed Steele is one amiable guy. This year he celebrates his 50th anniversary in the wine industry, and you don’t last that long in any endeavor, and especially not one that depends on consumers, if you’re not pleasant.

My most recent column was about the most exciting wines I had last year, including the soul-stirring, almost Burgundian Chardonnays from Bodega Catena Zapata’s Adrianna Vineyard in Argentina.

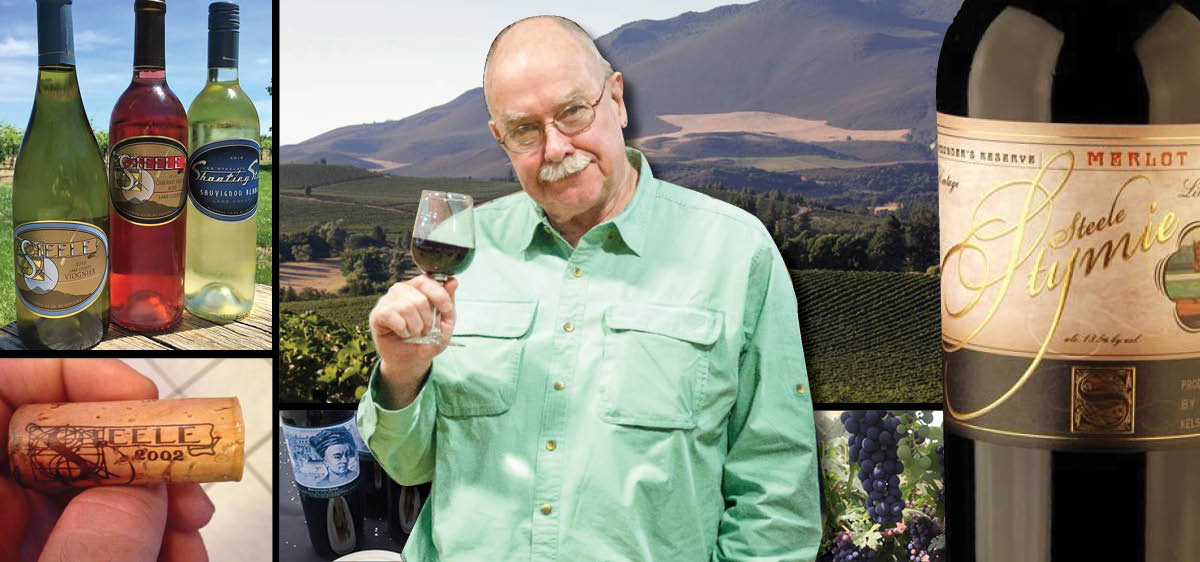

Steele’s wines, from his own 27-year-old eponymous winery, Steele Wines in Kelseyville in Lake County, California, aren’t drop-everything stunners. Instead, they’re something that is even rarer today: They are tasty, honest, true-to-varietal wines that are affordable. The 40 or so different wines he makes, from 20 grape varieties, range from around $10—I haven’t tried those—to around $40. The bottles that the winery recently sent me were $14 to $21, everyday wines. He has four labels: Steele, Stymie, Shooting Star and Writer’s Block, which he helps his son, Quincy, make. We have enjoyed Steele-labeled Pinot Noir and Chardonnay from the famous Bien Nacido vineyard in Santa Barbara for years; the others were new to us. Steele’s total production is 60,000 cases.

How can he deliver such quality at everyday-enjoyment prices? I asked him when I called him last week in Jacksonville, Florida, where he and his wife spend a couple of months every year.

“The vineyards are the key,” Steele, 72, told me. He sources the grapes from the four vineyards he owns in Lake County, and he has long-term leases with like-minded grape growers. “I’ve dealt with a lot of them for over 30 years, some 35 years maybe.”

“Consistency of grape supply is the key. And don’t manipulate the wine much. Nowdays there are all kinds of bells and whistles that you can employ. I believe in a basic approach to winemaking that’s not too complicated,” he said.

Steele has worked with grapes from virtually every major wine region in California and several regions in Washington and Oregon. His work experience includes several months in 1968 and 1969 working the crush and living at the Napa minimalist temple, Stony Hill; 10 years at Edmeades Winery in Mendocino; followed by helping Jess Jackson get Kendall-Jackson Winery get off the ground in Santa Rosa in 1982 and riding that juggernaut for nine years before establishing Steele Wines. Not only did Steele help make the first vintage of the KJ Vintners Reserve Chardonnay that became the country’s best-selling Chardonnay, but Steele was also the first winemaker at Jackson’s cult Cabernet Sauvignon producer, Cardinale, which I wrote about here.

His first effort there, its inaugural 1983 vintage, made a year after the winery was founded, won best of show at the California State Fair in 1986. Steele also was a consulting winemaker with Ste. Michelle Wine Estates in Woodinville, Washington, for more than a decade and at Fess Parker Winery in Los Olivos, in Santa Barbara wine country. A trip to Austria led him to fall hard for Blaufrankisch. He calls his Shooting Star version Blue Franc. A trip to Burgundy led him to Aligote, which he makes with grapes grown in Washington.

His first effort there, its inaugural 1983 vintage, made a year after the winery was founded, won best of show at the California State Fair in 1986. Steele also was a consulting winemaker with Ste. Michelle Wine Estates in Woodinville, Washington, for more than a decade and at Fess Parker Winery in Los Olivos, in Santa Barbara wine country. A trip to Austria led him to fall hard for Blaufrankisch. He calls his Shooting Star version Blue Franc. A trip to Burgundy led him to Aligote, which he makes with grapes grown in Washington.

So Steele knows a lot about grapes. He’s respected for the way he works with small lots and his ability to blend, a skill he notably demonstrated at K-J. He keeps single-vineyard grapes separate until blending just before bottling. Although Shooting Star wines are his entry-level line, they share the same grape source as the higher-end Steele labeled wines, but are fermented in stainless steel or get a short time in oak and should be drunk young. The single vineyard designate or specific vineyard blend Steeles get more oak aging and will age for eight to 10 years, according to the winery.

Of course, being in Lake County, north of Napa County and east of Mendocino County, is a tremendous help in keeping costs down. There are only 32 wineries in Lake County now and about 10,000 acres of grapes. Jackson’s first vineyard was there and winemakers in Napa and Sonoma are warming to its potential. “People are planting. It’s a very good region and land prices, compared to Napa and Sonoma, are extremely attractive,” Steele told me. “Sonoma has about 50,000 acres in vines and Napa about 45,000 so we’re still a drop in the bucket.

But, he added, “You have to go over a mountain to get to Lake County and because we never developed infrastructure, like hotels, it remains a remote spot.”

Jedediah Tecumseh Steele’s story is as colorful as his name. His father was a copy editor at newspapers and “a fan of thoroughbred horses,” Steele told me. His dad’s winnings on a horse called Stymie were generous enough to finance the family’s move, with four children, from 121st Street between Amsterdam and Broadway in upper Manhattan, to San Francisco in 1950. Stymie was said to never give up a lead after gaining it, which resulted, some say, in the inclusion of the stallion’s name in English lexicon, as in, “They’ve been stymied again!” However Merriam-Webster says it originated in Scotland and is associated with golf! Stymie labels are Steele’s reserve wines, a Merlot, $42, and a Syrah, $36, which I haven’t tried.

As fate would have it, his parents’ neighbors in San Francisco were Fred and Eleanor McCrea, who were in the early stages of growing their Stony Hill Winery on Spring Mountain in Napa Valley into a producer of one of the California’s first cult wines, a lean, bright, intense Chardonnay. (I wrote about them here.

Steele’s father, who wrote well-regarded historical biographies for the last 25 years of his life under the pseudonym Lately Thomas and clearly had a flair with names, had lived in France and loved fine wine and food. Steele shared this vivid memory of his Dad with Mike Dunne of the Sacramento Bee: “I remember cases of Clos de Vougeot and Bordeaux first growths being delivered to our back door whenever he had received an advance for one of his books.”

Steele’s father, who wrote well-regarded historical biographies for the last 25 years of his life under the pseudonym Lately Thomas and clearly had a flair with names, had lived in France and loved fine wine and food. Steele shared this vivid memory of his Dad with Mike Dunne of the Sacramento Bee: “I remember cases of Clos de Vougeot and Bordeaux first growths being delivered to our back door whenever he had received an advance for one of his books.”

Of Fred and Eleanor McCrae, he told me, “My parents knew them. They owned Stony Hill Winery. At the time, one way to get the wines was you had to get on the mailing list. But they really liked you to pick up the wine at the winery; that was sort of the protocol, although they did ship to some people. So once a year we would go up there and pick up our allocation of Chardonnay or whatever it was, so I had met them.”

Here, Steele, who stands 6’4”, reminds me that “this was the ’60s in San Francisco and there was a back-to-the country kind of atmosphere pervading. As a youngster, I liked the country. I used to go camping and stuff. So when I talked about working in a winery, Dad suggested the McCraes. It was a job in the country at a winery and it sounded good to me so that’s where I ended up. I didn’t have any idea that it would become a vocation at that point.”

He had studied psychology on an athletic scholarship (basketball) at Gonzaga University in Spokane, graduating in 1967.

“Back in the late ’60s, I would not say that there was a lot of future in the wine business. I don’t think there were 10 wineries in Napa. I know Bob Trinchero at Sutter Home and we were talking a number of years ago and he said, ‘Man, I don’t understand this whole business. When I was a kid my parents were telling me to get out of the wine business, become a doctor or a lawyer or a dentist. But now all of these doctors and lawyers and dentists want to be winemakers,’” Steele recalled, chuckling.

“If you were in a wine family and you had an opportunity to pursue another profession, that’s usually the way you went. It was nothing like it is today,” he said.

The minimalist way that Fred McCrae and his winery team worked left an indelible impression on Steele and informs the way he works with grapes today. That means hand-picking grapes, using standard, non-GMO yeasts, natural fermentation and eschewing extra additives or enzymes.

Following Gonzaga, he worked as a brakeman at the train station in Oakland, waiting to hear if he’d be off to Vietnam. When he didn’t pass his physical because he had “a physical limitation,” he said, he decided to get a master’s degree in oenology at UC-Davis. Among his classmates were “two Wente Brothers, Tim Mondavi and Merry Edwards,” he told me. Upon graduation, he was invited to be a partner, winemaker and vineyard manager at Edmeades Winery in Philo, a remote corner of Mendocino in Alexander Valley. He had met Deron Edmeades, son of the vineyard’s owner, in the ’60s while fishing in the area. We have fond memories of Edmeades’ charming Zinfandels.

Steele had made Edmeades’ wines for a decade when he got a call that changed his life from Paul Dolan, winemaker at Fetzer and a friend. “‘There’s this guy in Lake County, the next county over, and he’s in a jam. He needs some help. I sort of helped him get started, but can you help him out?’’’ Steele recalled Dolan saying.

“So I went over and met Mr. Jackson and helped him for three months, which became six months,” Steele said. “The winery was a mess. I helped straightened it out, and then he offered me a fulltime gig, which I did. I was there for nine years.”

But he wasn’t Kendall-Jackson’s first winemaker. “There was a kid that he hired that lasted two or three months,” Steele said. “I worked on the first vintage, basically put it together.”

Jackson, who died in 2011 at the age of 81, had said the first Vintners Reserve Chardonnay was a blend that experienced a stuck fermentation, “a mistake,” which left the wine a little sweet, agreeably it turns out, to huge numbers of wine drinkers, including the late First Lady, Nancy Reagan. By the end of the 1980s, people were buying 550,000 cases a year of it, according to Dunne.

“After nine vintages we were up to one million cases, growing like crazy and had wineries all over the state,” Steele told me. “I felt more like an air traffic controller than a winemaker, trying to coordinate all of the stuff. I just thought it was too big for my style.”

“There certainly is a degree of power and professional prestige in turning out six-figure boxes of good Chardonnay annually, but there is something about the days at Stony Hill that I felt I needed back. The touch, the feel, the intimate contact with the wine is necessary to me as a winemaker in the practice of my craft. I had lost this intimacy at Kendall-Jackson,” Steele told Andrew Lampasone of The Wine Watch.

But after Steele left in 1990, Jackson sued him, charging that he had shared the “secret” method of making the Chardonnay with his new employer, owners of Chateau Ste. Michelle at the time, and interfered with K-J’s business relationships by negotiating with its grape growers to provide grapes to Steele’s new venture. Steele sued Jackson for what he said was the remainder of a consultant’s fee they had agreed on.

It was an acrimonious battle that, I’ve read, wine industry people still debate. First, was there such a thing as a “secret” method to make the wine, and if so, who should rightly own it, the winemaker or the winery owner? Jackson, “in a surprise ruling,” according to the New York Times, won his claims, but he had to pay Steele what Steele said he was owed.

When I asked about the lawsuits, Steele said, “That was interesting. I think it was emblematic of the changes in the business. With my generation, when we started out, we were very altruistic, collegial. We were not considered a world-class wine region when I got into the business.

“I remember going to Burgundy in 1966. The wine community there was very pleasant and polite, but I sort of felt like I was in a like a side-show. ‘Oh look, he’s an interesting winemaker from California! He has three legs and nine eyes.’ Again it was very cordial but it’s like they didn’t really take you for real. Then the wines started to get better, and then there’s the Judgment of Paris and then off we go. But it was very altruistic for everyone when we started.”

Winemakers shared information with each other. “We had a common goal to gain international recognition,” he added, “and the Jackson suit thing sort of ended a lot of that, the congenial atmosphere.”

“We got along fairly well, you know, but he had a certain style of doing business which I never thought would impact me but it finally did. That was just his MO, how he handled situations,” Steele said.

Without missing much of a beat, Steele and his then-wife, Marie, who had been Jackson’s bookkeeper, went about growing Steele Wines and in 1996 moved the business into a larger space, the former Mt. Konocti Winery. Steele has remarried and he and his employees are among Marie’s best customers at a restaurant she owns near his home, The Saw Shop. He has a daughter who is an intellectual property lawyer and son, Quincy, who married a French woman in August and lives in Burgundy.

Shooting Star’s name is associated with the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, who was born in 1768 and opposed white settlements in North America and is said to have derived some of greatness from being born during a meteor shower, “under the sign of the shooting star.” Steele’s label reads, “My father, an American historian of Tecumseh’s era, had a great respect for this native American hero and gave me the middle name of Tecumseh.”

From 2015 and all $14, the Shooting Star Pinot Noir, Lake County, was light on its feet, peppery and aromatic; the Shooting Star Merlot from Lake County was smooth, with good minerals and earth and surprisingly dry; and the Shooting Star Zinfandel from Mendocino County was tasty, with light, pure red-berry flavors. One source of the Zinfandel grapes was the Pacini Vineyard, planted in 1943 and dry-farmed. The wine was so balanced that we didn’t know, until looking at the label, that it was 15.8% alcohol. Amazing.

The Writer’s Block is Quincy’s “baby,” his dad said. Because he’s in Burgundy so much, he leaves guidelines for his fermentation protocol for his father and team and then he returns to blend. His 2015 Pinot Noir from Lake County was so drinkable that we went through it quickly and marveled that it was only $17. It’s the kind of wine that your guests would pour themselves and that you’d need lots of bottles of. The writer featured on the back label is Robert Mailer Anderson.

The Writer’s Block is Quincy’s “baby,” his dad said. Because he’s in Burgundy so much, he leaves guidelines for his fermentation protocol for his father and team and then he returns to blend. His 2015 Pinot Noir from Lake County was so drinkable that we went through it quickly and marveled that it was only $17. It’s the kind of wine that your guests would pour themselves and that you’d need lots of bottles of. The writer featured on the back label is Robert Mailer Anderson.

I got to try Steele labeled 2013 and 2014 Pinot Noir from Santa Barbara County (Bien Nacido’s young Block F and lower elevation Goodchild Vineyard) against the Steele Carneros 2013 and 2014 Pinot Noir from Sangiacomo Vineyards, whose fruit Steele has used since its first vintage, 1991. That wine was a revelation because he had not made a Pinot Noir during the nine years at Kendall-Jackson and it has consistently been a best-seller for the winery. Each at $21, these wines were excellent values. The 2013 Carneros was more cherry than strawberry, bright, and both it and the 2014 were juicy with great acidity, good tannins and beautiful noses. The Santa Barbara County wines, both vintages, were dark, richer and juicy with good earth, a dash of cola and minerals. Good California Pinot Noir for $21? Awesome.

Honest and affordable California wines are still possible. That’s news we can all embrace.

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. Dottie and John are well-known from their many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck.

Read more of Dorothy J. Gaiter on Grape Collective.

Main banner art by Piers Parlett