It’s a wonderful thing to see a business, any business, stay true to its founding principles. Trends come and go; outside factors can impinge; stresses and strains can undermine. It’s all the more amazing when it’s a family-owned business, and a farming enterprise, vulnerable to the vagaries of Mother Nature.

Smith-Madrone Vineyards & Winery, high atop Spring Mountain in St. Helena in Napa Valley, is such a business. Back in 1999, we had its 1984 Cabernet Sauvignon for Thanksgiving and pronounced it then—15 years old—robust and fruity enough that it could age. We’d paid $25 for that wine on February 28, 1998, according to our notes, a real deal. A couple of weeks ago, we had the 2013 Cabernet Sauvignon, around $50, sent to us by the winery. It was so elegant and true, with ripe black fruits, cedar, rich earth and minerals that cut through it all like a blade, that we geeked out about it for hours. This wine could easily reach 20 years without breaking a sweat. Smith-Madrone, a pioneering winery 46 years old this year, was still nailing it, and with a finesse that suggested ease.

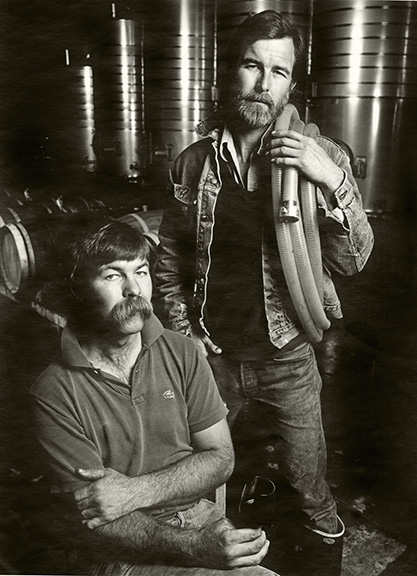

(Photo of Stuart and Charles Smith)

Duh, you might be thinking. Of course Napa Cabernets are classy and special. We wish that were always true. But over the past several years we have found it increasingly difficult to find a truly classy Napa Cabernet, and certainly not at $50 or less.

Stuart Smith, 68, founded the 4,000-case winery in 1971 when he was 22 with a degree in economics from Berkeley and some enology classes at UC-Davis. While studying for his Master’s at Davis, Stuart was the first teaching assistant for Maynard A. Amerine, a plant physiologist widely considered the father of American wine because he helped revive the California wine industry post-Prohibition, and Vernon Singleton, a trailblazing expert in the chemical compounds, like tannins, that affect a wine’s taste, color and texture. Eager to begin making wine, Stuart left short of his degree and, with the help of family and friends, purchased 200 acres of forest on beautiful Spring Mountain. The land had been part of an original 550-acre homestead that more than a century before had included vineyards. Stuart’s brother, Charles F. Smith III, 73, who also went to Berkeley and had taken classes at Davis, left a teaching job to join Stuart in 1973. Today, Stuart’s title is general partner, enologist; Charles is winemaker; and Stuart’s son Sam, 29, is assistant winemaker.

The Madrone half of the winery’s name is from the Madrone trees, evergreens with red bark, white flowers and, during fall, orange-red berries. About 40 acres of the 200-acre ranch is vineyards. The winery makes three estate-grown, mostly dry-farmed wines: currently, the 2013 Cabernet Sauvignon; the 2014 Chardonnay, $32; and the 2014 Riesling, $30. Smith-Madrone’s inaugural wine was its 1977 Riesling and that wine won a prestigious competition in Europe in 1979, putting the winery on the map in this country. It’s still famous for its Riesling. Charles, it turns out, was extremely fond of German Rieslings, interesting as the family is descended from German immigrants, who came here in 1730. In addition, they grow Merlot and Cabernet Franc (smithmadrone.com). The Smiths also make a small-production Cabernet Sauvignon-based wine called Cook’s Flat Reserve, named after the first owner of the land, George Cook, and a special vineyard. The 2009 current release sells for $200, (cooksflatreserve.com).

(Sam, Stuart and Charles Smith photo by Mike Dunne)

When I asked Stuart about working for 46 years with his brother, he said, “It’s like a marriage. It is a marriage. It’s the best of times and it gets a little gnarly at times.” Their dad worked with one of his brothers in insurance so at least they had a model for a sibling professional relationship.

After Stuart purchased the mountain property, he hired a company to clear some of the trees. Some neighbors weren’t happy about Stuart’s logging and another property-owner’s logging and the county quickly passed a moratorium on logging, according to a fine piece on Smith-Madrone in the Napa Valley Register in 2013. But it turned out that the county had overstepped, the newspaper reported, so Stuart prevailed. Other winemakers have followed Stuart’s example, putting their stakes in mountain property. Stuart is now celebrated as an expert on mountain viticulture.

The mountain appealed to Stuart, he said, quoting the Roman poet Virgil in Latin, on Bacchus loving the mountains, the sunny hills. The vineyards in the Spring Mountain district are at elevations between 1,300 and 2,000 feet above sea level, on steep slopes of soils that are volcanic-based with shale and limestone and loam. With panoramic exposures, Stuart chose which direction he wanted for each variety of grapes. All of that thought and care went to ruin when phylloxera hit Smith-Madrone and many of their neighbors in Napa. They had to replant beginning in 2000.

“Once you get over the emotional distress of seeing our vineyard die, you see the silver-lining-behind-the-darkest-cloud concept,” Stuart told me when I called him the other day. “Whoopee! I get to replant with all of the technology that has transpired over the past several years. It’s an opportunity. But you don’t see that in the beginning.”

The vineyards at Smith Madrone photo by Kelly Puleio

He told me he used that do-over opportunity to change the direction of some of the vineyard’s rows, spacing and trellising to better take advantage of the sun and the cool of the evenings, to better help the grapes ripen.

The 1984 Cabernet that John and I had in 1999 was 100% Cabernet Sauvignon. “That was a lovely vintage, a lovely wine,” Stuart recalled, adding that the 1984 Riesling, which they most recently tasted last year, was “equally good.”

Beginning in 2000, with the replanting program, Smith-Madrone’s Cabernet Sauvignons have been blends. The composition changes depending on what type of vintage they experience. The Smiths are proud of their emphasis on terroir, putting in the bottle what Nature gives them without manipulation, sometimes with no filtering and fining, and trying to do it in an environmentally sustainable way. The 2013 Cabernet is 82% Cabernet Sauvignon, 12% Cabernet Franc, which gave it real edge, and 6% Merlot, aged in French oak.

Looking back, with all of the wisdom of his 46 years making wine, what advice would he give a winemaker starting out, I asked him.

“Follow your passion,” Stuart said. “There’s always room for a new idea in the wine business, always ever-changing. But the fundamentals of wine are unassailable: Good wine can only come from good grapes. The best grapes, we think, come from the mountains.”

The following are previously unpublished excerpts from an interview Grape Collective conducted with Stuart Smith in 2014.

Stuart Smith photographed by Kelly Puleio

Grape Collective: How did you get involved with the wine business?

Stuart Smith: I started this in 1970. Well, we closed on the property in early 1971. My background is that I went to U.C. Berkeley in the middle of the '60s and then didn't want to go back to Los Angeles, where I grew up, and took a class out at U.C. Davis, liked it, applied for grad school, and was accepted and did my master's work out there. Put together a little partnership of family and friends in the fall of 1970 and we got this piece of property. The history of the property goes back to the 1880s when it was all in vineyards and there was a row of olive trees, just off camera, that was planted at the time, so they're about a 130 years old. The vineyard was abandoned, as pretty much everything on Spring Mountain was abandoned, because of phylloxera around the turn of the 20th century. When I first walked the property in the fall of 1970 this was a very dense, impenetrable forest.

Now there were grape stakes throughout all of the forest, but it was as much poison oak and Douglas fir and oaks and Madrones as anything else. A matter of fact, we had to get a commercial logging permit to reclaim the forest, and out of that my brother and I decided to call it Smith-Madrone, because Smith, as I like to say, is not a great southern European wine name, and Madrone is a tree here, and so Smith-Madrone sounds fine. We cleared the property in 1971, we planted it in 1972 to four varieties of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Riesling, we used to call it Johannisberg Riesling, and Cabernet Sauvignon. In the mid '80s we grafted over the Pinot Noir, it certainly wasn't doing as well as we would like, and we stuck with Chardonnay, Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon. Then in the late '90s we planted Merlot and Cabernet Franc for blending into the Cabernet. We grow five varietals and we make basically three wines plus a reserve.

Tell us, starting in the '70s, I mean this was not the sexy area. How did you pick Spring Mountain? I mean now everybody loves this area, it's an internationally known wine area, but back then I imagine it must've been a bit of a risk or at least it wasn't conventional thinking to move up here.

There are certain principles in life and in winemaking and in grape growing and I adhere to those principles and that is that you can't make good wine from bad quality grapes. You have to have the best grapes and, in my opinion, then, as it is now, the best grapes come from the mountains. "Bacchus loves the hills" is an old, old saying. I think if you look at why we're here on Spring Mountain and why we're here in Napa Valley it's because Napa Valley had the reputation for making the best wines in California, and Sprint Mountain has the reputation for making the best wines in the Napa Valley, and so I didn't want to go anywhere else. Now, in the 40 years plus that I've been here there's been a lot of transition and a lot of changes and a lot of the folks that had vineyards in the valley floor have now come to the mountains, because, in part, I hope, for what we've done.

It's a lot of work. It's a lot more work than being down in the valley floor. It's somewhere, maybe, two or three times, maybe four times the work of being in the valley floor. We have rocks. We have trees that die. We have trees that fall over. We have 50% more rainfall than in the valley floor. All of these things are things that we have to deal with. As an example, in the beginning we use to cultivate everything, then starting in the mid '70s we went to, way before most anybody else, we went to non-till. Soil erosion is something that we simply will not stand for, and so creating a vineyard which is sustainable is very important to us, and, as I like to say, the things that we've learned, BMPs, best management practices.

(Charles and Stuart Smith photographed by Mike Dunne)

We're a much better farmer today than we were 30 years ago; 30 years ago we were a better farmer than we were 20 years ago, and we will continue to improve as technology gives us the skills to move forward we can do things in the vineyard that we could never do, even imagine 40 years ago. As an example we can farm all of the vineyard with a four wheel drive wheel tractor. Well, in 1972, '71, '70, the idea of having a tractor on the mountains was ludicrous; I mean it was a certain destination of death. Now we just take it for granted. Now we still keep our crawlers, but viticulture is very important up here. It's something that's very near and dear to my heart, and there's been a lot of changes in viticulture in the 40 years, as there has been in the winery. We constantly are changing and challenging conventional thought and wisdom.

There's kind of a movement afoot across Napa Valley and the world looking for kind of wacky farming paradigms, and they will fade, because they're not based on science and you have to use science. One of the great things about California, and what allowed us to go from a sleepy little backyard wine industry into kind of preeminent national recognition is the use of science. Europe got to where it is over centuries of trial and error, we took their trial and error and threw it up against science and we kept what was good and we jettisoned what wasn't, and then there's a little bit of art that you throw in there, so it really is a combination of both science and art. Fundamentally there are fundamentals of growing grapes and making wine that you simply can't get around, and you have to grow grapes in the right location, in the right soil, in the right site, and you have to have the right attitude.

Wine grape farming is very different from any other kind of farming. If you're growing corn or wheat or rye, you judge yourself on success by the number of bushels that you bring out. In wine grape farming you're really dealing with a secondary approach. It really doesn't matter what the vineyards look like, what you're really doing is you're farming for wine. Wine, after all, is fundamentally agricultural, it comes out of the soil, and that's the great thing about making wine and growing grapes, is you get to play in dirt and then drink beautiful wine at the dining room table. There's really no product, that I have yet run into, which is as elegant and beautiful and life-giving as wine.

What do you do that you would consider sustainable farming and how does that reflect in the wine?

Well, sustainable farming is a concept which is, as most of the farming paradigms are out there, is somewhat loosely defined, but the idea of sustainable farming is farming in a manner in which you can commercially, economically farm a ranch for hundreds of years. The idea that it's a short-term issue is ridiculous. Farming should be long-term and you should be able to farm to where generations from now will be able to farm the same piece of property in a sustainable manner also. In other words, that it grows, it produces a good crop and it's economically viable. For us, these are concepts that are always changing, ever moving, as I mentioned, BMPs, best management practices, are always evolving.

The Spring Mountain view at Smith Madrone photograph by Christopher Plante

Besides permanent cover crops, we put in subterranean pipes, where all the water goes, especially the roads, the roads are the biggest problem, because they're impermeable surface, so you want to get that water off the roads and underground and into a pipe system and down into a reservoir, where we recapture it, or we'll put it into what we call a sediment retention basin, which is basically an area where you take a non-point source of water, which is rain, it goes into a pipe, you now have a point source, you then dump it into a basin, a reservoir or basin, large, small. It goes into a pipe that then is another point source, but the pipe then goes into a spreader situation, where you have pipes that go out and just above the unaltered natural forest and the water than gently percolates back into the soil and goes down and now you have a no point situation and there are no rivets or gullies or anything of that nature.

Our goal is that eventually, we hope, and we're pretty close, to where no water will run off our property ever, except in a natural creek or drainage system. All of our roofs, all of our concrete, all of our roads, all of our vineyards will be kept on the property. Then the other one too is that we don't use pesticides here. We're isolated, the idea of using pesticides, and you have to qualify that term very closely. We haven't used pesticides ever as a bug killer, because we're willing to put up with a certain level of damage and other bugs will come in and eat them, other bugs will come in and eat them and so you have kind of a dynamic system going on in the vineyard. Integrated pest management might be another word for it.

We do believe very strongly in being able to use something like Roundup underneath the vines, I think that's very important, and frankly I would argue strenuously against anybody who says it's not environmental, because, in fact, when you start looking at alternatives to that you've got to look at the carbon footprint of vineyard workers coming to the vineyard, all of the things that go into an impractical way of dealing with the environment. One time I had a blog going and the guy says, "Well, I use a thing called Paraquat," and I go, "My god, Paraquat is dangerous as hell." He goes, "Yeah, I just got out of the hospital." I'm going, "You're lucky to get out of the hospital." Where things like Roundup, it may adapt eventually, but in the interim it is a great product that allows for safe use and an economically viable, and I think, sustainable use in the vineyards.

As far as keeping mildew out, we sulfur dust, like most anybody else. From an environmental point of view, sulfur dust I find somewhat ironic, because all the sulfur dust that's used in all of the vineyards, organic or biodynamic, is a petroleum-based product. If you really look at the four paradigms of farming out there, you've got organic, biodynamic, you got sustainable, and you've got conventional or traditional. The biodynamic and the organic people are using petrochemicals, so if you're going to use petrochemicals here why not use them over there? The reason is because they can't grow grapes without elemental sulfur, and that comes out of oil. I'm sorry, guys.

(Banner artwork by Piers Parlett from a photo by Kelly Puleio)