The Pfalz

If you want concrete eggs and amphorae, funked-up pet-nats and glou, keep looking. But if you aren’t too cool to (also) love the most achingly beautiful, classical, elegant, full-bodied, extract-rich, earthy wines, above all dry Rieslings from some of the best vineyards anywhere, you’re home.

The Pfalz is just an hour-and-a-half drive southwest from Frankfurt, but it has a definite south-of-the-Alps feel. With a surprisingly Mediterranean climate, olive, fig, and almond trees abound, thriving in the long, dry summers. In small villages, window boxes spill color over tidy sills and timeworn shutters. Handsome, well-proportioned houses beckon with wide, rounded-arch doorways leading into gracious, leafy courtyards. A sea of vines covers the short, hilly span between village boundary and forest edge. The expanse of the Haart mountains a gently reassuring backdrop rather than an austere menace.

The Pfalz is just an hour-and-a-half drive southwest from Frankfurt, but it has a definite south-of-the-Alps feel. With a surprisingly Mediterranean climate, olive, fig, and almond trees abound, thriving in the long, dry summers. In small villages, window boxes spill color over tidy sills and timeworn shutters. Handsome, well-proportioned houses beckon with wide, rounded-arch doorways leading into gracious, leafy courtyards. A sea of vines covers the short, hilly span between village boundary and forest edge. The expanse of the Haart mountains a gently reassuring backdrop rather than an austere menace.

This amplitude and harmony is all there in the wines of the Pfalz. You'll find an unmistakable through line of full-bodied generosity, earthiness, and piquancy, and above all reliably balanced dryness. Frank Schoonmaker, in his essential 1956 guide, The Wines of Germany, used the term Bodengeschmack (earth flavor) to indicate what he found to be a disagreeably heavy character in some of the lowlier Pfalz wines. But I found earthiness to be an essential hallmark of the region. It is what sets these wines, especially the Rieslings, apart, especially from their shimmering mineral-spring cousins in the Mosel. There is a pleasingly dusty mouthfeel that amplifies the extract and salinity of the wines. This in turn complements the sagey herbaceousness, delicate orchard fruit, and occasional tropical fruit notes. The wines can be wonderfully succulent, but rarely cross the line to opulence.

Producers in the Pfalz were early to recognize the region’s suitability for dry Riesling and already had considerable experience with it when the Trockenwelle (dry wine craze) first swept through Germany about 20 years ago. Now they have brought it to perfection. But this is not to ignore the Pinots Blanc, Gris, and Noir, Scheurebe, Sauvignon Blanc, Muskateller, Rieslaner, Dornfelder, or the sophisticated sparklers known here as Sekt.

In the market

Yet the wines can be vexingly hard to find in the U.S. One of every five bottles of German wine is produced in the Pfalz, a quarter of that is exported, and the U.S. is a key target market. But the numbers do not add up to a robust presence in shops or restaurants. An informal survey of retailers in New York City, one of wine’s most sophisticated and diversified markets, reveals that to fill a case with a dozen different bottles from the region would require trips to at least five wine stores. The choices on restaurant lists — and these are wines that definitely find their highest calling at the table — are few compared with those from other German regions.

I asked German wine importer and expert Terry Theise why this is. “I wonder if the uniformity of the Pfalz as an overwhelmingly dry-wine region plays a role. Riesling is already a niche, and dry Riesling is a niche among Rieslings, at least over here,” he mused. He also thinks the fruit and charm of Mosel and Nahe wines “are easier for today’s buyers to grok” relative to the “earthier and more sinewy” wines of the Pfalz, making the latter a harder sell. Moreover, “I’m not convinced that regions matter that much to the current market or to the (mostly) millennial buyers.” He takes the position that most consumers are producer focused and may not even be aware of the region in which an estate whose wines they like is located. I get it. Riesling can be so very many things and knowing which of those you like, and on which occasions, takes some experience. But I’d argue the Pfalz should be the German region that does get consumers to ask for it by name — the wines have a recognizable profile that cuts across producer lines and improves even the modestly informed drinker’s chances of hitting on a fine, dry, food-friendly wine.

Lay of the land

The Pfalz is tucked in the southwestern corner of Germany. To put it in the context of other German regions, it's farther north than Baden, roughly parallel with the Mosel, bounded by Rheinhessen above and Alsace below.  It is essentially one long band of vineyards, edged to the west by the Haardt Mountains — an extension of the Vosges — and to the east by the broad Rhine plain. Look closely at a good wine atlas and you’ll see the Pfalz technically extends just over the French border, the result of vacillating political borders and long-held vineyard ownership rights. Within the Pfalz there are two main subregions, Mittelhaardt Deutsche Weinstrasse to the north and Südliche Weinstrasse to the south, with the small city of Neustadt, itself home to grand estates, foremost Müller-Catoir, at the midpoint.

It is essentially one long band of vineyards, edged to the west by the Haardt Mountains — an extension of the Vosges — and to the east by the broad Rhine plain. Look closely at a good wine atlas and you’ll see the Pfalz technically extends just over the French border, the result of vacillating political borders and long-held vineyard ownership rights. Within the Pfalz there are two main subregions, Mittelhaardt Deutsche Weinstrasse to the north and Südliche Weinstrasse to the south, with the small city of Neustadt, itself home to grand estates, foremost Müller-Catoir, at the midpoint.

Half a century ago, Frank Schoonmaker wrote, “In order to buy Rheinpfalz [as the region was called until 1992] wines intelligently, it is essential to be familiar not only with the town names and the vineyard names but with the producers’ names as well.” This has not changed. Wachenheim, Forst, Deidesheim, and Ruppertsberg are the quartet of Mittelhaardt villages Schoonmaker deemed “incomparable” and they remain so to this day. But to these must be added the names of villages north and south: Schweigen, Birkweil, Kallstadt, Kindenheim, Ungstein, each with its own distinct soil type, microclimate, favored varieties, and producer styles.

Forst stands alone

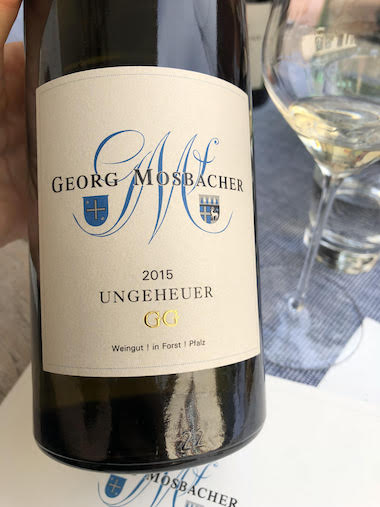

If there is one village in the Pfalz with a claim to preeminence, it is Forst. It takes its name from the forest that rises just behind its world-famous vineyards.  The main cobblestone street is lined with decorous houses, many belonging to great producers like Georg Mosbacher and Heinrich Spindler, whose backyards are the legendary grand crus of Pechstein, Jesuitengarten, Ungeheuer, Freundstück, and Kirchenstück. The vineyards climb gently toward the forest edge, a lightly rumpled dark green quilt of parcels stitched together by narrow footpaths. Ungeheuer is the largest, at 29 hectares, and is, as all these great vineyards are, carefully parceled out among top estates. In the words of Schoonmaker again: “It is hardly surprising that the quantity of wine available from a given vineyard, producer and year, is in almost all cases extremely limited, and often amounts to no more than a single cask of 1,200 liters.” Kirchenstück, at just under 4 hectares, enjoys the greatest reputation. It is exalted for its limestone and basalt soils, its gentle slope, and low sandstone walls that absorb the sun’s warmth during the day and gently release it at night. Most distinctive perhaps is Pechstein, whose soils are predominantly volcanic basalt, famed for giving a lush tropical character and smoky, saline qualities to its wines. Generally, Forst vineyards are known for their ripe, fragrant, full-bodied but nuanced Rieslings of great aging potential.

The main cobblestone street is lined with decorous houses, many belonging to great producers like Georg Mosbacher and Heinrich Spindler, whose backyards are the legendary grand crus of Pechstein, Jesuitengarten, Ungeheuer, Freundstück, and Kirchenstück. The vineyards climb gently toward the forest edge, a lightly rumpled dark green quilt of parcels stitched together by narrow footpaths. Ungeheuer is the largest, at 29 hectares, and is, as all these great vineyards are, carefully parceled out among top estates. In the words of Schoonmaker again: “It is hardly surprising that the quantity of wine available from a given vineyard, producer and year, is in almost all cases extremely limited, and often amounts to no more than a single cask of 1,200 liters.” Kirchenstück, at just under 4 hectares, enjoys the greatest reputation. It is exalted for its limestone and basalt soils, its gentle slope, and low sandstone walls that absorb the sun’s warmth during the day and gently release it at night. Most distinctive perhaps is Pechstein, whose soils are predominantly volcanic basalt, famed for giving a lush tropical character and smoky, saline qualities to its wines. Generally, Forst vineyards are known for their ripe, fragrant, full-bodied but nuanced Rieslings of great aging potential.

A pocket history

Over the centuries, geography has been a blessing and a curse to the Pfalz. It has given the region some of the greatest wine terroirs in Europe. But it has also made the Pfalz a dangerous crossroads for destructive religious and political battles. Traces of Roman viticulture point to the Pfalz’s early role as a supplier of drink to stationed legionnaires. The collapse of the Roman Empire left the Pfalz (which takes its name from the Latin palatium, meaning palace) in a vinous dark age. But by the 7th century, enough wine was being made that the powerful prince bishop of Speyer saw fit to tithe it. The first vineyard site designations were recorded in the 12th and 13th centuries. Some, like Müller-Catoir’s “Breumelgarten,” still in use to this day, date to this time. The Thirty Years War and its chaotic aftermath were particularly disastrous for the Pfalz. French soldiers ravaged villages and vineyards and the Napoleonic secularization that followed splintered vineyard holdings. In 1744, a later prince bishop of Speyer decreed that then-common Elbling should be replaced with “noble” varieties, including Riesling, in his prized vineyards in and around Deidesheim, laying the groundwork for Riesling’s rise here and throughout the Pfalz.

The “comet vintage” of 1811, so called for a comet that was visible in the night sky that year, shone a spotlight on the stellar quality (and quantity) Pfalz Rieslings were capable of. When the Kingdom of Bavaria established its dominion over the Pfalz in 1816, tax maps were drawn up and vineyards revalued. The 1828 vineyard classification map assessed Forst’s Kirchenstück as the most valuable of all. The 19th century was a high point for German Riesling, especially from the Pfalz: When the world turned its eye on the spectacular inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869, they saw von Buhl Riesling flowing for the toast.

But by the end of the 19th century, vineyards in the Pfalz had, along with most in Europe, succumbed to the deadly vine root louse, phylloxera. Soon after, a school of viticulture was established in Neustadt to encourage research and educate growers about how and what to replant. A long period of widespread recultivation ensued. In 1935, in an effort to promote travel to and through the region (n.b. the year), the Deutsche Weinstrasse (German Wine Route) was established, linking the Pfalz’s 40 wine villages.

In the 1980s, Flurbereinigung (vineyard reorganization) caught up with the Pfalz. This massive government-led effort to help producers (whether they wanted help or not) consolidate and upgrade the infrastructure of their vineyard parcels has been ongoing in Germany for a century. When it reached the Pfalz, old vines were ripped out and prized parcels went unused during the time it took to regrade, lay new paths, walls, and drainage channels. The estates and the government split the costs of the work, but producers were left with the task of replanting and had to wait out the unproductive youth of their new vines. When I raised the topic with Sabine Mosbacher of Weingut Georg Mosbacher in Forst, she shrugged and said, “We didn’t really have a choice. In the long term, it was a good thing.”

By the 1990s, with Flurbereinigung behind them and new plantings gradually reaching maturity, a small number of producers, led by Hans-Günther Schwarz, long-time cellar master at Müller-Catoir in Neustadt, set their sights on returning the premiere sites of the Pfalz to their historic greatness.  Hansjörg Rebholz of Ökonomierat Rebholz in Siebeldingen did the same for vineyards like Kastanienbusch in the southern Pfalz. This was when the region fully tapped into its potential and identity as a source of extraordinary dry wines.

Hansjörg Rebholz of Ökonomierat Rebholz in Siebeldingen did the same for vineyards like Kastanienbusch in the southern Pfalz. This was when the region fully tapped into its potential and identity as a source of extraordinary dry wines.

Terroir

The Pfalz is widely regarded as an extension of Alsace — same mountain range, warm, dry, climate, kaleidoscopic soils, penchant for dry, full-bodied wines. But the Pfalz has a geologic history peculiar to itself, due to the ancient collapse of the Rhine river basin, which disrupted geologic layers and even allowed for an incursion of volcanic basalt. Colored sandstone, shell limestone, marls, and Rotliegend (a unique sequence of rock strata, usually sandstone, from the early Permian period) form the base layer. Later marine deposits weathered into loam loess soils. Basalt is a distinctive feature of the famed Pechstein (pitchstone) vineyard, but also, thanks to human action, other Forst vineyards such as the Ungeheuer. In the 19th century, when the area’s basalt was quarried, fragments were hauled to vineyards around Forst and scattered among the vines both to help collect heat and give greater mineral character to the wines. (“What else should they do with it?,” Sabine Mosbacher asks wryly.) Most important for the Mittelhaardt area are red and yellow sandstones, which whose course texture seems to translate directly into a pleasing raspiness in the wines. Sandstone is important not just in the vineyards but around them, as many of the best, such as Hohenmorgen in Deidesheim, are enclosed by low sandstone walls that retain and gently reradiate warmth. To the north and south of Mittelhaardt, limestone plays a much more important role, making those areas somewhat better suited to the Pinot family.

As John Szabo has written in Volcanic Wines, the Pfalz is one of the world’s best sites for exploring “the influence of bedrock on wine profile.” Pechstein gives aromatic Rieslings redolent of ripe stone fruit, with a fascinatingly saline smokiness. Kallstadt’s Saumagen, a lime pit in Roman times, is dominated by limestone and lime marl soils that translate into intense, coiled wines that langorously unspool their tremendous potential. The Ungstein Weilberg’s Roterde (red earth) clay loam gives rich wines, tending toward tropical and lime characters. Birkweil’s Kastanienbusch, with its mix of lime, marl, colored sandstones and even slate in a warm, sheltered spot yields powerful, but elegantly herbaceous Rieslings. So much to explore in this single region alone.

“Germany’s workshop”

In the Middle Ages, up to about 1550, red varieties predominated in what is now Germany. After that, the “little ice age” made conditions too cool for red grapes and just right for whites, especially Riesling. In the modern era, the Pfalz has become what Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson call “Germany’s workshop” of grape varieties. Pfalz producers who belong to the VDP are only permitted to label three varieties as Grosses Gewächs (grand cru dry wines): Riesling, Pinot Blanc, and Pinot Noir, suggesting these grapes reach their highest potential here.

Among Pfalz whites, Riesling reigns supreme, trailed by the elegant Pinots Blanc and Gris, zesty white Scheurebe, aromatic Muskateller, and golden-toned Sauvignon Blanc, as well as Rieslaner for exotically aromatic sweet wines. Just a tiny amount of Scheurebe is now grown in Germany, but producers like Jan Eymael at Weingut Pfeffingen in Ungstein specialize in the grape, delivering wonderfully dry, focussed, earthy wines redolent of sage, grapefruit, and black currant.

The Pfalz is now Germany’s largest red wine producing region, with Pinot Noir playing Riesling’s role in this category. Juicy Dornfelder, and a handful of international varieties follow close behind. Pinot Noir rendered as still or sparkling blanc de noir is a popular style here and there were many fresh, grippy, delicious offerings to choose from in this category.

For now, experimental varieties remain on the fringe. Sabine Mosbacher has planted a small parcel of the rare crossing Cabernet Blanc as “an idea for the future.” She and her husband Jürgen farm organically, and they were attracted to the potential of this Cabernet Sauvignon x “undisclosed disease-resistant variety” (as Jancis Robinson, et al.’s Wine Grapes has it) to give a peppery, fresh, herbaceous white wine that would require fewer treatments in the vineyard.

Plantings of aromatic grapes like Gewürztraminer and Muskateller and various German crossings well suited to higher sweetness levels have waned with the popularity of this style, even as producers like Bassermann-Jordan and Koehler-Ruprecht produce stellar sweet and dry versions, respectively, today. Axel Neiss of Weingut Neiss in Kindenheim noted “many old Palatinate varieties are being ripped out and replaced with late-ripening varieties from southern Europe to take advantage of the warmer climate and to see how they work in our hotter, drier summers.”

In the cellar

The cellars of the Pfalz are some of the oldest and most magnificent I’ve visited. Von Buhl’s tunnelling underground networks date to the time when the prince bishop of Speyer used them to store provisions. Bassermann-Jordan’s burrow seemingly endlessly beneath Deidesheim and once connected with those of neighobring Von Winning.  Hidden passages and side chambers are filled with massive old wooden presses from the early 19th century, relics from long before and since, alluding to the cellar’s central role in Deidesheim history. Allegedly, an 1811 "comet Riesling" lurks in there somewhere, too.

Hidden passages and side chambers are filled with massive old wooden presses from the early 19th century, relics from long before and since, alluding to the cellar’s central role in Deidesheim history. Allegedly, an 1811 "comet Riesling" lurks in there somewhere, too.

In every cellar, you will see row upon row of the same handsome, traditional vessel: Stück and Doppelstück. These casks of German, French, or Austria oak hold the traditional measures of 1200 liters (Stück) or 2400 liters (Doppelstück) favored for the gentle oxygen exchange they facilitate during the maturation of the wines. Most winemakers follow time-honored practices: gentle pressing, long lees time, little racking, bottling close to a full year after harvest, and in some cases giving the bottles another year in cellar before release. Some estates, like Bürklin-Wolf, von Buhl and Jülg, work with native yeasts even for their most prized parcels, but on a selective and sometimes complementary basis with commercial yeasts.

Of coops and Liebfraumilch

The Pfalz is a giant in German wine production, with every third bottle of German wine purchased in the country coming from the region. More than 100 million vines and close to 3,000 winegrowers are at home here. The Pfalz has 13 coops, long responsible for churning out the region’s value wines. Die Weinmacher and Deutsches Weintor are the two biggest, making wines to send abroad and to fill German supermarket shelves. No doubt much of it goes into the typical dimpled Pfalz pint glasses that are used to hold white wine spritzers known here as Schoppenschorle — “like mother’s milk for us Pfälzer!,” Stefanie Weegmüller noted cheerfully.

In the past, this productivity has sometimes been a liability, as coops churned out simple inexpensive wine, a good deal of which was sopped up by the infamous Liebfraumilch. Demand for this once wildly popular wine has plummeted in recent years, though one Pfalz producer, Christoph Hammel, sees in it a tradition worth preserving — and a glittering marketing opportunity. “It is a wine that by law can only be produced in the Pfalz and the Rhine regions. We ruined it by making it like toast bread: industrial, sweet, cheap shit. It’s the victim of heartless mass production. But it can be a perfect Sunday afternoon wine. Fresh, relatively low alcohol, off dry, ripe.” A blend of Müller-Thurgau, Riesling, and Scheurebe, Hammel’s provocative Black Madonna Liebfraumilch '17 is super fresh, sagey, peachy, earthy, creamy, long with a balanced sweetness that may change your mind about the style.

Changes

The most critical development here, as everywhere, is climate change. Stefanie Weegmüller of Weingut Weegmüller in Neustadt, who has been making wine for 34 years, recalled that when she was a child, “harvests happened up to mid-November — sometimes in the snow.” But she hasn’t harvested past mid-October for 20 years now. Last year was the earliest harvest in Pfalz history. This year picking had already begun as this article went to print in the third week of August 2018. Harvest times are generally becoming more erratic: At Reichsrat von Buhl in Deidesheim, the last grapes of the 2017 harvest were brought in on September 28; in 2013, the picking had not even begun on that date. Pfalz vintners are grappling with the question of how to handle these fluctuations in terms of vineyard management and labor needs, both of which are becoming more difficult to calculate. Axel Neiss of Weingut Neiss in Kindenheim, noted that in the 2018 growing season, there had been only two rainfalls, but both were drenching downpours. The sudden rain bursts can damage the old, handbuilt dry walls that surround his, and other producers’, most prized parcels, adding the cost of finding and paying trained labor to repair them.  Growers are also reevaluating their vineyards to see which may be the “big winners” of climate change, as Mosbacher says of her historically cooler Musenhang parcel.

Growers are also reevaluating their vineyards to see which may be the “big winners” of climate change, as Mosbacher says of her historically cooler Musenhang parcel.

Aside from this, the Pfalz seems immune to most of the trends now sweeping other wine regions. I saw no anfora or concrete eggs, heard no mention of “natural wine,” saw only one serious skin contact wine (Friedrich Becker’s skin contact Grauburgunder ‘17, which was presented as “a very conservative orange wine”), and sensed generally mixed feelings about spontaneous fermentations.

For those who consider organics and biodynamics a trend, rather than a paradigm shift, I did see a very serious commitment to responsible farming. The embrace of biodynamics is especially remarkable among the big estates: Reichsrat von Buhl, Dr. Bürklin-Wolf, and Ökonomierat Rebholz. Producers like Dr. Bürklin-Wolf say they particularly value the way biodynamics amplifies terroir expression — all-important in the intensely terroir-driven vineyards around Deidesheim and Forst. Other large producers like Bassermann-Jordan are certified organic and employing selective biodynamic practices, noting that these have brought more even ripening, and yields more consistent year to year. For various reasons, the word “biodynamic” may not appear on the label, but the odds are high that a Pfalz wine will be farmed at least responsibly and sensitively, if not fully biodynamically.

Generational change is another theme, though it feels more evolutionary than revolutionary here. Johannes Jülg, who has been cellar master at his family’s estate since 2011 but works in tandem with his father, summed it up like this, “My father and I love the same wines in the end. But our way of production is different. We spend more time in the vineyards now, we buy more barrels, we use more native yeasts.”

The demands of the German market are of course most germane to producers here. The thirst for dry Riesling that has predominated for past 20 years is an obvious influence. Another is the apparently insatiable German thirst for bubbles, who boast the highest per-capita consumption of sparkling wine worldwide. While Sekt can be the cheap and cheerful German counterpart to Prosecco or Cava, top-quality Sekt is another matter and is emerging as an important category for the Pfalz. New classification standards just released by the VDP are meant to spotlight the quality and lees aging of VDP members’ more serious méthode champenoise bottlings. Pfalz Sekt is typically made from Riesling or Pinot Noir in blanc de noir or brut rose styles. I found that Reichsrat von Buhl’s Sekts cut an especially impressive figure, as befits an estate now headed by the former winemaker at Bollinger, Mathieu Kauffmann. The ‘15 Riesling Sekt Brut I tasted was bone dry in the house style, with a classic brioche nose from 15 months on the lees, in tension with beautiful sage and citrus notes.

Wines for food

The cooking of the Pfalz is rich and relaxed, hearty, rustic, and delicious. One afternoon, in the welcoming, leafy courtyard at Weingut Jülg, which is also home to the Jülg family restaurant in Schweigen, we were treated to a meal that showcased what Pfalz wines do best: join you at the table. Winemaker Johannes Jülg was juggling his baby daughter in one arm, serving dishes cooked up by his 82-year-old grandmother in the other, and somehow pouring and discussing his wines at the same time.  His grandmother’s heaping Saumagen platter was a revelation. Saumagen — a speciality of the Pfalz made of sow’s stomach stuffed with assorted pig parts and well spiced with nutmeg and marjoram — was thickly sliced and lavished with liver dumplings, more pork sausage, and butter-roasted potatoes. This is where these broad, dry, earthy, spicy wines find their highest calling: in playing off deeply flavorsome, savory, fatty dishes. Yet, on another evening, at the Eymael’s family’s Hofffest (winery celebration) at their Weingut Pfeffingen in Ungstein, where tents and picnic tables filled a pleasant side yard, as a hundred or so mostly white haired locals gathered to enjoy the tradition of simple fare and excellent Pfeffingen wine, I was surprised to find Pfeffingen’s Ungstein Dry Scheurebe 2017 was a superb match for a snack of spicy guacamole — a pairing I’ll be repeating at home as soon as I lay my hands on another bottle. As they say in the Pfalz: Zum Wohl!

His grandmother’s heaping Saumagen platter was a revelation. Saumagen — a speciality of the Pfalz made of sow’s stomach stuffed with assorted pig parts and well spiced with nutmeg and marjoram — was thickly sliced and lavished with liver dumplings, more pork sausage, and butter-roasted potatoes. This is where these broad, dry, earthy, spicy wines find their highest calling: in playing off deeply flavorsome, savory, fatty dishes. Yet, on another evening, at the Eymael’s family’s Hofffest (winery celebration) at their Weingut Pfeffingen in Ungstein, where tents and picnic tables filled a pleasant side yard, as a hundred or so mostly white haired locals gathered to enjoy the tradition of simple fare and excellent Pfeffingen wine, I was surprised to find Pfeffingen’s Ungstein Dry Scheurebe 2017 was a superb match for a snack of spicy guacamole — a pairing I’ll be repeating at home as soon as I lay my hands on another bottle. As they say in the Pfalz: Zum Wohl!

Top Picks

Dr. Bürklin-Wolf Wachenheim Riesling 2013

This village-level Riesling spend a year on the fine lees and is now floral, spicy, savory. So much tropical fruit on the nose. Super, long, penetrating perfectly integrated flavors, creamy mouthfeel but still shot through with acidity, beeswax texture, fineness tempering power.

Weingut Neiss Spätburgunder “Blanc de Noir” 2017

I loved the clean herbaceous, nose, grippy, mineral 3D structure, restrained fruit and super phenolics. It’s made from 50% saignee method, 50% pressed grapes.

Weingut Neiss Weissburgunder “Burgweg” 2015

Single vineyard bottling of this delicately herbaceous, super fresh and acid-driven white. With notes of barely ripe white peach, shiso leaf and a long, clean finish, this is like diving into a pile of freshly laundered linens.

Weingut Georg Mosbacher Riesling “Leinhöhle” ‘16

Another single vineyard standout. Very delicate apricot and blossom, gorgeous and ripe. Ready to go now.

Weingut Georg Mosbacher Riesling “Musenhang” ‘16

For a micro terroir study, contrast Musenhang with Leinhöhle. This bottle is super crisp, spicy, with lime zest, pure, deep, concentrated flavors coming from the loany, lime-inflected soils. Line drive out of the park.

Weingut Georg Mosbacher Riesling Ungeheuer GG ‘16

From Sabine Mosbacher’s 1.7 hectare parcel of the legendary Forst vineyard, with its mix of colored sandstones and strewn basalt, comes one gorgeous Riesling. Herbaceous, almost resinous, with lemon and grapefruit pith and zest notes. Saline, deep, rounded, though less faceted than the Musenhang.

Von Winning Riesling Ungeheuer GG ‘16

Another opportunity to compare and contrast at a micro level. Von Winning’s Ungeheuer has more power, dry extract and spice notes but every bit as much elegance as Mosbacher’s. See if you agree.

Müller-Catoir Riesling Bürgergarten “Im Beumel” GG ‘15

From Müller-Catoir’s monopole “Breumel in den Garten”, one of the oldest vineyards in the Pfalz, first planted 700 years ago. The colored sandstone and loam-loess soils combined give a shimmeringly nuanced interpretation of characteristic Pfalz earthiness, herbaceous, and delicate stone fruit notes.

Pfeffingen Dry Scheurebe 2017

Earthy, juicy, herbaceous, super fresh, lime, passionfruit, cassis. One of six or seven different styles of Scheu Jan Eymael makes at his family’s estate, which specializes in Riesling and this now rare. Eymael says his time working in Pessac-Leognan influences the style of his Scheu, and he looks for the creaminess of Semillon and the tropical freshness of Old World Sauvignon Blanc.

Pfeffingen Herrenberg Riesling GG ‘13

From a site favored by medieval dukes -- and it’s clear why. The limestone soils give a nose of petrol lime zest that is super aromatic and expressive. Dried honey, camomile, depth of flavor, super long finish. This is Pfalz wine at its finest.

Von Buhl Riesling Dry VDP Gutswein ‘17

Characteristic Pfalz nose with ziplining acids, palpable extract, white peach, sage and so much depth. This is von Buhl’s leading wine in the German market and you’ll understand why when you have it in your glass.

Von Buhl Deidesheimer Riesling Dry Ortswein ‘13

A high-acid vintage, says the producer, but this wine reads gloriously ripe and subtly, herbaceous. The fruit is so fresh and primary but undergirded by a leesy creaminess and electric acids. Designed to be a long-distance runner. Now with fives years of age, it feels just off the starting blocks.

Von Buhl Deidesheimer Herrgottsacker Riesling VDP Erste Lage ‘16

Clean, driving, with notes of grapefruit and white peach. Super long finish of fruit and mineral.

Von Buhl Kieselberg Riesling GG ‘16

From the gravel plateau of red and yellow sandstone that brings saltiness and silkiness to the wine, while the penetrating evening sun exposure ensures super ripeness of the grapes. The nose of sage and yellow plum, the leesiness, spice and earth tones all wrap up with an ultra long finish. Only 0.5g RS.

Weingut Jülg Riesling Kalkmergel Dry ‘17

From limestone and clay soils, we tasted an example bottled that morning, so it was marked by a the zip of dissolved CO2 but no less enjoyable for that. Creamy, apricot notes, saline finish and the perfect partner to a rich lunch of earthy Pfalz meat dishes.

Weingut Jülg Weissburgunder Kalkmergel Dry ‘16

Apricot and white peach aromas, super fresh and creamy on the palate, grippy and phenolic.

Weingut Heinrich Spindler Musenhang Riesling ‘15

Superb, taut, intensely flavored, with lime zest, creamy lemon curd, and lilting minerality. From one of the cooler sites in Forst, the “muse’s slope” with loam-limestone soils. In general, the ‘15s from the Pfalz are drinking very well right now, but I expect this and many of the best examples have long lives ahead of them.

Hammel & Cie Liebfraumilch “Black Madonna” Premium Edition ‘17

If you’re going to drink Liebfraumilch, this should be the one. Winemaker Christoph Hammel sees this white blend as “an icon of German history” that wants to revive. Using a traditional blend of Müller-Thurgau, Riesling, and Scheurebe, Hammel’s provocative Black Madonna Liebfraumilch is super fresh, sagey, peachy, earthy, creamy, and surprisingly long.

Special thanks to Wines of Germany/Deutsches Wein Institut for providing the author with the opportunity to deepen her knowledge of Pfalz wines on a visit to the region in July 2018.

Map courtesy of Reichsrat von Buhl

Additional sources:

Wine Atlas of Germany, Braatz, Sautter, Swoboda, 2014

Oxford Companion to Wine, Robinson, Harding, 2015

Deutsches Weininstitut

Read more from Valerie Kathawala on Grape Collective.

Banner by Piers Parlett