Having got my hands on a fascinating old wine book, I thought I'd dig further into what the Kiwi wine scene looked like a couple of generations back. The result shows not only the challenging moment it found itself in, but also highlighted some notable social stereotypes of the time…

Fifty years ago, the Land of the Long White Cloud did not enjoy its current image for the production of high-quality, low-yielding wines, for export around the world. As we'll see, quality issues, coupled with availability and cultural acceptance of the drink, were a hindrance on the growth of the industry. But where did it all start?

Although Colonialist and Maori antagoniser-in-chief James Busby was one of the earliest viticulturalists in the 1840s (having already established himself as one of the founding fathers of the Australian wine industry), it is widely accepted that Anglican missionary Samuel Marsden directed the planting of the first grapes on Kiwi soil. The most senior Chaplain to the New South Wales government, he was also responsible for introducing new species of livestock, fruit trees and vegetables to New Zealand. Under the guidance of Marsden, in 1819 Superintendent of Agriculture Charles Gordon planted the first grapevines on Bay of Islands sites such as Rangihoua, Kerikeri, Russell and Waitangi.

(Arrival of Samuel Marsden at Bay of Islands, 1814)

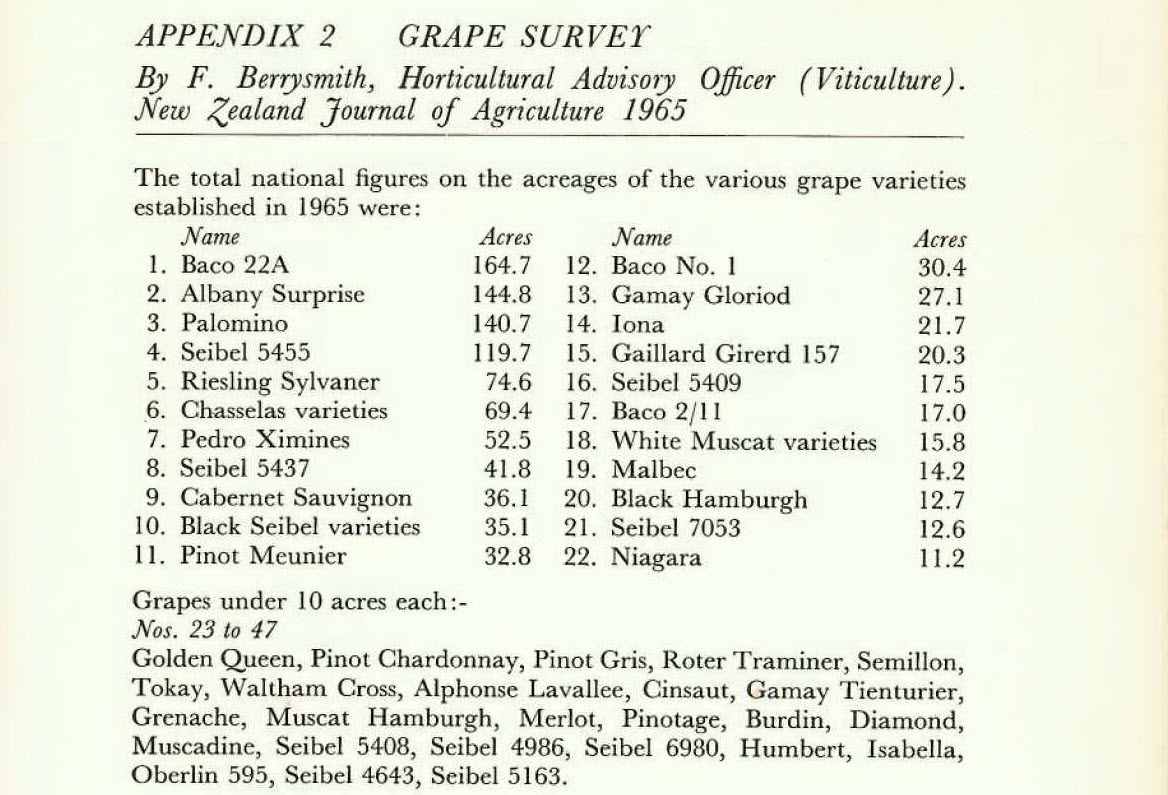

Fast forward around 150 years, as the seeds for the modern-day boom were being sown, and in 1965 the below grapes were the most-grown in the country. Not heard of Baco 22A? If you like Armagnac, that fiery brandy (distilled wine) from the south-west of France, this science-experiment of a grape is its primary ingredient. The main stand-out from the table is how Sauvignon Blanc, New Zealand's current calling card on the international stage, is missing: not introduced to the country until later in the 70s, initially to be blended with the Müller-Thurgau grape, it now accounts for nearly three-quarters of nationwide production.

(left: 1965 Grape Survey, NZ Journal of Agriculture)

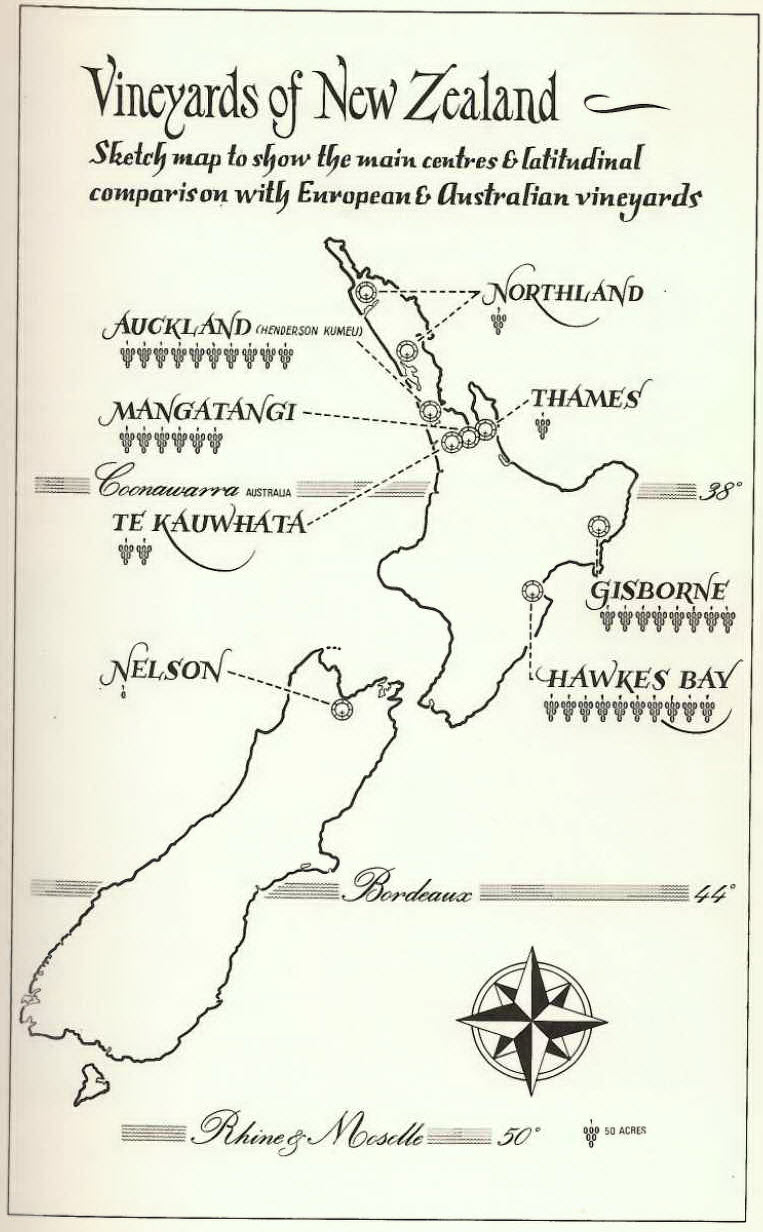

And where was it all being produced? By looking at the map below, amazingly we can see how three of New Zealand's major wine-producing regions today were not even seen as being important: Martinborough, Central Otago, and the grand daddy of them all - Marlborough, the modern-day engine room of the country's Sauvignon Blanc output, and two-thirds of total national yield.

(Right: Wine regions, early 1970s (Wine in New Zealand, Frank Thorpy, 1971)

So was any of the wine worth drinking back then? Albany Surprise, Seibel 5437 and Gamay Gloroid don't sound particularly appealing, and according to the internet, Waltham Cross is a town in southern England. In Wine in New Zealand, published in 1971, Frank Thorpy asked "How good are our wines?". To start he classified quality into four groups:

•Ordinary ("no pretensions to quality...with a definite alcoholic strength")

•Standard ("blended uniformly from year to year")

•Fine ("wines made from great care and distinction, usually one grape type")

•Great ("quality equivalent to classical grapes from select vineyards in France")

For the wines of the time, his conclusions were not encouraging. Thorpy described New Zealand as having no Great or Fine wines, "perhaps some Standard wines, with the bulk fitting into the category of Ordinary". Hmm. Using another definition, as laid down by Australian author Dr Max Lake in his book Classic Wines of Australia, he also explored whether or not a Kiwi wine could be designated as a "Classic" by being of "highest quality for that country, established for more than ten years, consistent during that period, and of a particular style".

Even at the higher end of the market, consistency of quality seemed to be a real problem. McWilliam's, a leading winemaker of the day, produced a wine called Bakano (pictured above left), a mash-up of hybrid grapes and "a touch of Cabernet". It had solicited high hopes of vintage quality year after year, and was certainly regarded as one of the best wines of the era, but upon opening the 1956 vintage, the author found "it had not improved as much as a wine of that age should", with the '62 and '65 having "no bouquet and without a great deal of character". Oh dear. No Classic status either, then.

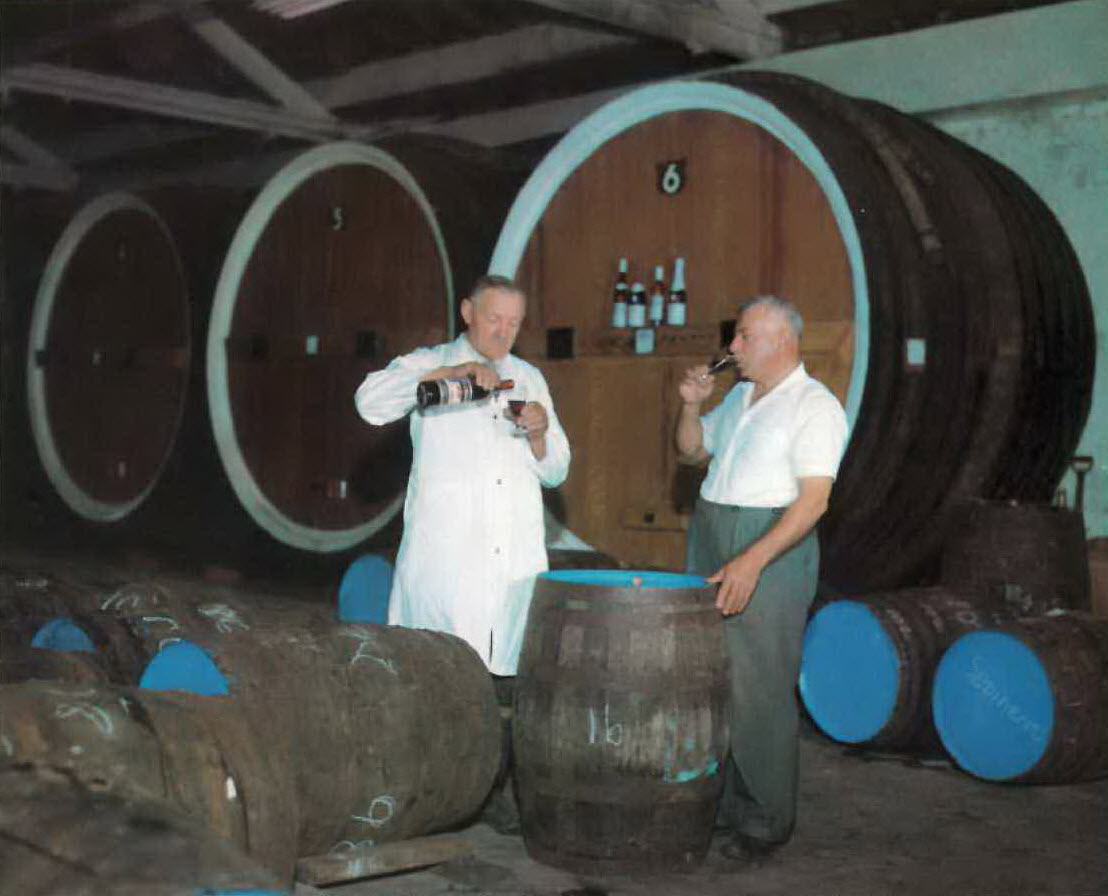

Two of the founding fathers of New Zealand's wine industry: the Corbans

Quality issues aside, by looking at the social habits of the day it is also easy to understand why wine struggled to get traction in the 60s and 70s. As my own mother-in-law (Welsh, but settled in Wellington in 1968) explains, "when we arrived in New Zealand I had never even tried wine. It wasn't really available. We used to drink rum and Coke, brandy and dry, beer, that sort of thing. By the mid-70s we would maybe have a bottle of wine at a restaurant as a treat, but it wasn't until the early 80s we started to have wine at home - usually Chardonnay in cask. In the early days it wasn't sold in supermarkets, and independent merchants weren't really around".

Cultural stereotypes were unfortunately pervasive, too. "Traditionally the host, not the hostess, pours the wine. If the 'host' happens to be a woman, then she should ask a male guest to do the pouring", Thorpy recommended in Wine in New Zealand. Moreover: "Rosé wines are becoming popular as they are light and innocuous, of a pleasing colour and are ideal for women's luncheons".

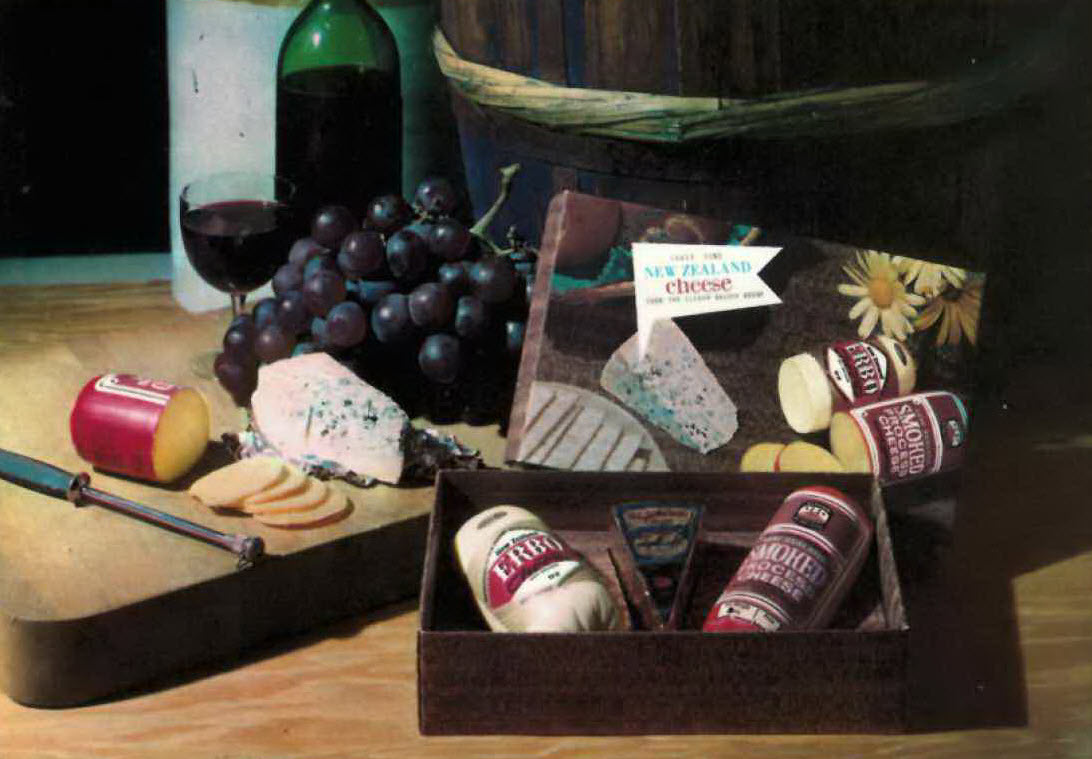

In addition, the country certainly did not enjoy its strong food-and-wine dynamic as it does today. As Thorpy goes on, "for the hostess looking for an easy and fashionable way to entertain, wine and cheese tastings are the vogue. Cheese acts as a good foil for wine tasting, but it should be cut up into cubes and served with toothpicks to prevent the smell of cheese from your fingers overpowering the wine". Continuing: "More wine should be used by the housewife in everyday cooking”.

("A happy combination of of NZ wine, grapes and cheeses" (Wine in New Zealand)

Overall, Thorpy summed up the situation by using the overseas market as his yardstick:

We would be deluding ourselves if we were to think we could export wines in any quantity at the moment. Having visited and tasted wines in most countries of the world, I think New Zealand would find it extremely difficult to compete. We must first put our house in order.

And put their house in order is exactly what New Zealand's wine trade went on to do. As renowned writer Michael Cooper commented in his landmark 2002 publication Wine Atlas of New Zealand, in the 1980s and 90s, amid a backdrop of large-player consolidation and the growth of artisanal entrants, "winemakers switched from cheap, everyday drinking wine to premium-quality wine with export potential".

With a focus on producing quality and a move away from hybrid grapes, although the country is not in the top ten wine-producing nations globally, according to the New Zealand Winegrowers' 2016 Annual Report Kiwi wines now have a significant export footprint, vastly outstripping domestic demand, with markets such as the US and UK leading consumers.

In further recognition of the consistency now being achieved from single varietal-single location wines, exactly what Max Lake was attempting to define, at the 2010 International Pinot Noir Conference, Ata Rangi (Martinborough) and Felton Road (Central Otago), left, were bestowed the title of Tipuranga Teitei o Aotearoa, which translates from Maori as 'Great Growth of New Zealand'. Decanter awarded NZ a total of seven Platinum medals in their 2016 World Wine Awards, two more than South Africa (which produces 4 times the amount of wine). The above-linked NZW Annual Report also provides a multitude of evidence that documents the marketing efforts being made, the research being carried out...and the plaudits being earned.

To finish, and again going back in time, in thinking about the modern practice of keeping wine in fancy wine fridges and the sort of bottles we keep at home for both everyday and "special" drinking, Frank Thorpy makes some excellent recommendations about what he felt should be de rigeur in the late 60s and early 70s:

For the person who wishes to maintain a small cellar for entertaining purposes...may I suggest the following; obtainable from any wine merchant:

•3 bottles of Dry Sherry

•1 bottle of Medium Dry Sherry

•8 bottles of Dry White table

•6 bottles of Rosé table wine

•12 bottles of Red table wine

•3 bottles of Sparkling wine

•3 bottles of Port, Muscat or Madeira or a full rich Sherry

"A small wine cellar of one's own", including a Montana "Chablis" (right)

Although New Zealand still has a long way to go — even for the well-established Cloudy Bay, 2015 was only their 30th vintage — as this look-back has shown, a country can go through a vinous transformation and create an image based on quality and accuracy in their winemaking. It'll be a pleasure to see how the next generation will play out.

——————

David is a Hong-based writer. In addition to his contributions to Grape Collective, he collaborates with merchants and distributors in his city, as well as writes his own blog, The 23rd Parallel. He holds a WSET Advanced Level certificate. You can follow him on Facebook here.