(Pictured above: East End vineyards, extending toward the sea)

“The problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.”1 I found myself applying this idea repeatedly to Long Island wine country during a recent visit. I admit to having brought along a few preconceptions of my own: Would a place that was a seaside vacation spot first and a wine region second tend toward opportunistic agritainment? Would the wines themselves be subsidiary to the winery “experience,” with more emphasis on style than site? Did an early stab at defining the region in terms of what it could be still account for the delay its discovery of true self?

I found some lingering truth to the stereotypes, but they are much less complete. Experimentation, not mimicry, is what drives the most thoughtful winemaking here now. Aspirational comparisons to Bordeaux have given way to a more grounded, confident identity. Careful growers are narrowing their focus on grape types best able to transmit the truest expressions of variety and site. Along with this, producers are embracing a wider range of vinification styles. It is easier to find well made wines, especially an ebullient lineup of sparkling, edging into the domain of heavier-handed, classically styled reds.

While some critics have pointed to vintage variation as liability for Long Island, ambitious producers take this capriciousness as a dare from Mother Nature. There are growers who hold tight to the belief that conventional farming is unavoidable here, but sustainable practices are gaining a toehold. Beyond this, a local custom crush facility is minimizing the risk smaller winemakers must take to get into the game. And a number of producers are jumping on the alt-pak wagon, exploring the viability of cans, kegs, and boxes as a way to connect with a younger market less attached to formality, more attached to fun.

In general, Long Island producers are signalling a greater willingness to confront the essential question of how to satisfy their loyal base of tasting room visitors and club members (still the most important market for Long Island wineries — some 50-75% of total sales) while pushing their wines closer to the decidedly cosmopolitan tastes of influential buyers, sommeliers, and critics, just 80 miles away in New York City.

Despite Long Island’s urban proximity and notable growth as a wine region (in just over 40 years, the number of licensed wineries has gone from zero to 70, and there are now some 2,500 acres under vine), it’s crucial to remember that the area is still in its relative infancy. Figuring things out is an essential part of any wine region’s process of maturing into its own sense of self. The wineries I visited span a range of styles — from earthy to elegant — that reflect the diverse thoughts about what Long Island winemaking is, or should be.

In the early 1970s, when aspiring winemakers first started buying up East End potato farms, these pioneers naturally had a limited understanding of their terroir, climate, and grapes. Just as in other new world wine regions, they began a long, necessary process of trial and error. Two big influences were the establishment of Cornell University’s local extension unit to advise the nascent industry and the New York State Farm Winery Act of 1976, which paved the way for commercial wineries to open to the public.

Around the same time, wealthy New Yorkers were reimagining the East End as their seaside playground. This would become the double-edged sword of Long Island winemaking: On one side, what could be a more logical, or intoxicating, extension of moneyed summer visitors and waves of beach tourists than building a homegrown wine industry to satisfy their thirst? On the other, what could be more limiting to the land needs of grape growers than the exorbitant cost of exclusive East End real estate (particularly on the South Fork, which is, consequently, home to just three of Long Island’s wineries)?

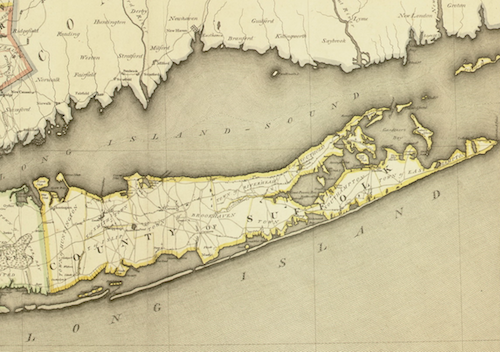

(Pictured left: 1802 map of Long Island's East End)

(Pictured left: 1802 map of Long Island's East End)

Nosing northeast into the open Atlantic and surrounded on three sides by water, the North and South Forks are the epitome of a maritime climate. Each fork is just six miles at its widest point, so no vine is more than a mile or two from the bay or the open sea. At Palmer Vineyards, on the North Fork, winemaker Miguel Martin says, “Water influences the season, what to grow, and how to grow.” At the time of my visit, water, in the form of two of the most destructive hurricanes in history, had just swamped Texas and the Caribbean, and a third storm, Jose, was bearing down on the eastern seaboard. With harvest imminent, growers were keeping a wary eye on the lowering skies. Roman Roth, veteran winemaker at the South Fork’s Wolffer Estate, acknowledges that “hurricanes and humidity” are his chief enemies here. Fortunately, recent major storms have tended to land after harvest and, even in the case of superstorms like Sandy, which hit Long Island hard in 2012, damage to East End vineyards and wineries has not been catastrophic.

Coastal humidity, by contrast, is a far less dramatic but constant threat. Standing at the edge of Palmer’s intensely verdant vineyards, on a September Saturday, a steady, skin-soaking mist offered ready proof of this. With so much moisture (in the forms of both humidity and rainfall), topography, soil type, and viticulture take on critical importance in ensuring the viability of vines here. At Wolffer, Roth pointed with pride to a gentle rise in the handsome vineyards that surround the imposing, chateau-style winery. A hillock is a rarity here, coveted for its water- and frost-shedding abilities. But most growers lack this luxury. “We wouldn’t exist on Long Island if we didn’t have incredibly well-draining soils,” acknowledges Kareem Massoud of the North Fork’s Paumanok.

(Pictured below, right: Soil cross section, Bedell Cellars)

The forks are essentially two enormous sandbars, the North topped with deep, sandy loam and the South with a somewhat heavier, denser layer of clay-banded sand and silt. These well-draining (but fertile) soil types and damp climate require exacting viticulture to control both vigor and disease pressures. “We’ve become obsessed and very meticulous about it,” Massoud says. As evidence of this, throughout the East End, you will see impecable trellising: row upon row of vines bearing robust grape clusters suspended below tidily manicured canopies. This upswept trellising style (“vertical shoot positioning,” or VSP), lifts the leaf canopy away from the grapes, allowing breezes to ventilate bunches and reduce humidity-born rot and mildew. Massoud again: “It’s no secret what a lot of growers are looking to do: We want every leaf, every grape cluster to be able to see see the sun, feel the wind.”

The forks are essentially two enormous sandbars, the North topped with deep, sandy loam and the South with a somewhat heavier, denser layer of clay-banded sand and silt. These well-draining (but fertile) soil types and damp climate require exacting viticulture to control both vigor and disease pressures. “We’ve become obsessed and very meticulous about it,” Massoud says. As evidence of this, throughout the East End, you will see impecable trellising: row upon row of vines bearing robust grape clusters suspended below tidily manicured canopies. This upswept trellising style (“vertical shoot positioning,” or VSP), lifts the leaf canopy away from the grapes, allowing breezes to ventilate bunches and reduce humidity-born rot and mildew. Massoud again: “It’s no secret what a lot of growers are looking to do: We want every leaf, every grape cluster to be able to see see the sun, feel the wind.”

If grapes can be kept healthy, moderate, year-round temperatures facilitate a luxuriously long growing season — more than a month longer than that of some other New York wine regions. This allows for the full development of flavors and aromas in the grapes, especially for late-ripening varieties such as Merlot, one of the early flagship grapes of the region.

Merlot and Chardonnay were some of the first varieties to go into East End vineyards. According to Gabriella Macari of Macari Vineyards on the North Fork, these were the grapes Cornell researchers told winemakers were “easy to grow.” They remain the most widely planted on Long Island, even as they increasingly yield vineyard space to newcomers from northern Italy, Austria and Germany. Today, an eclectic array of more than two dozen varieties are grown commercially here. “Diversity is what makes Long Island unique as a wine region,” says Palmer’s Miguel Martin, a sentiment echoed by his peers.

The experimental bent of Long Island grape planting can be traced to a source: Alice Wise, senior viticultural researcher at Cornell’s cooperative extension unit and research vineyard in Riverhead. Her grape trials on a tiny 2.5-acre plot have involved more than 50 Chardonnay, Merlot, and Cabernet Sauvignon clones and nearly as many novel grape varieties, including hybrids. “Over the years, the vineyard has been a microcosm of industry patterns and processes,” says Wise. "We choose varieties based on a number of criteria — suggestions from industry, academic colleagues and grapevine nurseries as well as descriptions in papers and references. "

“As a direct result of our trials,” Wise has written, “growers have established commercial plantings of six novel varieties: Dornfelder, Muscat Ottonel, Lemberger, Malvasia Bianca, Albarino and Barbera.” This research saves commercial vineyards enormous time and expense in screening for the most viable varieties. The most recent plantings include twp hybrids that may offer resistance to Long Island's disease pressures: Regent (a vinifera hybrid from Germany) and Petite Pearl (a hybrid from Minnesota) as well as the sturdy Georgian vinifera red grape, Saperavi. There are also more established trials under way with Italian vinifera varieties Arneis, Muscato Giallo, Verdejo and Vermentino. The grapes that emerge well suited to Long Island terroir may definine the next wave in Long Island wine.

Wise’s work affects viticultural practices among growers in other ways as well. She notes that “there is a genuine desire to embrace ‘greener’ products. That said, [the products] have to work and they have to be affordable.” Her research helps to identify which practices might meet these criteria.

Richard Olsen-Harbich, who has collaborated with Wise on her research, is a veteran North Fork winemaker at Bedell Cellars. He has made a life’s work of profiling the region’s climate and terroir and matching both to a “classic fit” of varieties. He acknowledges that being able to grow so many different varieties here “is a blessing and a curse.”

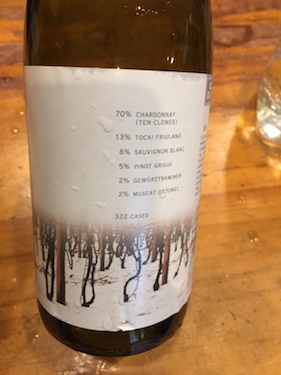

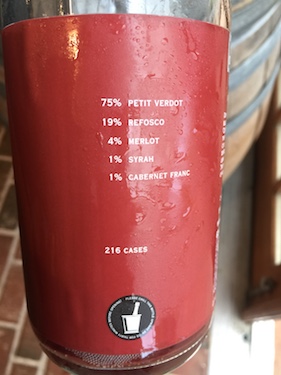

It’s clearly a blessing for winemakers who love exploring the edges, as Channing Daughters’ Chris Tracy does. Muscat, Lagrein, Dornfelder, Ribolla Gialla, Refosco, Malvasia… they’re all fodder for his investigations.

(Pictured left: Experimental blends like these define Channing Daughters' approach.)

“Aliveness, minerality, texture are super exciting,“ he enthuses, and these are precisely the elements so thrillingly at play in his wines. He is as much an experimenter with technique as with variety. He was way ahead of the curve on skin-contact wines and lately he’s gone full throttle on pet-nats, with 10 different traditional method bottlings made in the 2016 vintage alone. Now you’ll find them infiltrating by-the-glass pairings at more than one top New York restaurant.

At Macari Vineyards, UC Davis-trained winemaker Kelly Urbanik Koch age some Cab Franc and Sauvignon Blanc in concrete eggs to she channel energy into the texturally alluring Lifeforce bottlings. She, too, is looking harder at sparkling. “Horses” is a bubbly Cab Franc that harnesses the earthiness and fruit of this emblematic East End grape to finely beaded bubbles.

Some of this experimentation may also be attributable to vintage variation. “No two vintages are the same. It’s complete jazz,” Bedell’s Olsen-Harbich readily admits. Growers consider hot, dry vintages like 2010 and 2013 to be exceptionally good, delivering wines of exceptional concentration and purity for reds. Most recently, 2016 and 2017 were wetter, and tougher. Channing Daughters’ Tracy says part of the impetus for his exuberant lineup of pet-nats was the more challenging 2016 growing season. Paumanok’s Massoud says 2017 reminds him of 2011, when repeated vineyard treatments were essential and a significant portion of fruit needed to be dropped to preserve quality at the expense of yields.

Challenging vintages raise the question of how sustainably grapes can be grown here at all. The Long Island Sustainable Winegrowing program, launched in 2012 and the first of its kind in the east, encourages wineries to think critically about the long-term impact of their farming practices on soil and vine health, as well as the delicate maritime environment that surrounds them. It promotes innovations such as solar power, composting, and cover crops. However, it stops short of pushing for organic or biodynamic farming outright.

The Long Island producers I met seem to have grasped that part of capturing the interest of a generation of natural wine-focused consumers will mean committing to less intervention in the vineyard and the cellar. At Lieb Cellars and Palmer Vineyards on the North Fork, organic fertilizers and sprays are the norm. At Paumanok, winemaker Massoud characterizes his family’s approach as “focused on the goal, and open-minded about the methods.” These include integrated pest management, climate-responsive trellising, cover crops, and equipment such as mechanical weeders. The latter “may allow us to completely eliminate use of herbicides,” Massoud claims. “Our belief from day one has been to use the most effective, least toxic material available. We live on the property and drink water from our own well,” he points out, “and thus we have one more reason to be responsible custodians of the lands we farm.”

Macari Vineyards takes land stewardship even deeper. Joe Macari Jr. and his wife Alex started planting vines on their 500-acre Mattituck estate in 1995, raising their four children on the property. “We have a herd of cows that live on the vineyard, introduced in 1998 when my father started studying biodynamics with Alan York,” says Gabriella Macari. “We use cow manure for compost and to create ‘compost tea.’ While we aren't certified biodynamic, we believe that composting has helped increase the quality of our fruit. In addition to the cows, we have horses, goats, pigs and honeybees. We strongly feel that the biodiversity of our farm creates a unique and nourishing environment for our vines to thrive.”

If you accept a loose interpretation of biodynamics as the effort to create a diversified ecosystem that generates health and fertility as much as possible from within the farm itself, the Macaris come closer to achieving this than any other growers on Long Island. Still there are tough vintages when even the Macaris feel unable to farm without chemical intervention. This sort of pragmatism, informed by a sense of stewardship but ultimately dictated by crop viability, may strike some as incomplete. But it is clearly a step in the right direction.

Looking ahead, Bedell’s Harbich-Olsen forecasts, “We’ll continue to drill deeper into our terroir and fine-tune our winemaking. We’ll also continue to look at more eco-friendly, low impact/intervention techniques... and other techniques to improve local quality such as yield control, varietal and rootstock combinations and matching specific soil types to varieties for optimal quality.”

Many producers believe one chapter missing from the Long Island wine script is ageability — “the untold story” — in the words of Wolffer’s Roth. He presented a stellar magnum of 2000 Cab Franc to make his point. The fruit’s vivacity was still evident, but the wine had taken on an earthy, integrated suppleness. Few wineries have made a practice of holding back library wines as significantly as Wolffer has, but Channing Daughters and Macari share Roth’s belief and are doing more of it. Tracking the development of older vintages may be another interesting thread to follow here.

Long Island wines are reaching for a power all great wine regions possess: the consistent ability to take us to a place. In this case, the cool, uncertain maritime edge, where sea confronts shore and the outcome of the encounter is unknown. Wines that capture that tension will have shed the stereotype and revealed a truth.

Long Island Sparkling Wines to Try

Lively, delicious bubbles are becoming something of a signature for East End producers. Here are four that embody the diversity of styles on offer:

Macari “Horses” Sparkling Cabernet Franc 2015 ($26)

Single-vineyard Cab Franc from what has become an emblematic East End grape. Whole-cluster pressed, stainless-steel fermented, with a second fermentation in bottle. Dry, mineral, with the fruit and earthy directness of Cab Franc and a slight quinine note that makes it a beautiful refresher on summer days as well as a perfect accompaniment to richer autumn dishes.

Paumanok Petit Verdot Pet-Nat 2016 (club members only)

Paumanok is neatly striking the balance between tradition and avant garde. Petit Verdot usually plays a minor role in Bordeaux blends. Here it takes center stage in a monovarietal pet-net that is all playfulness. Redolent of violets and sage, with beautiful, pure-fruited plum flavors tinged with a dry herbaceousness, all shot through with a lively effervescent. Although this bottling is currently reserved for Paumanok wine club members only, after a taste you may find yourself signing up.

Wolffer “Cool as Well” Brut Blanc de Blanc 2013 ($35)

Best known for their wildly popular Rosés, Wolffer first made its reputation for displaying a deft hand with Chardonnay. This methode champenoise sparkler, made from some of Wolffer’s oldest Chardonnay vineyards, has energy and elegance to spare, with lively acidity, a bright line of minerality, lovely creamy mouthfeel and beautiful, fine-beaded effervescence. A winner for the holiday table.

Channing Daughters Tocai Friuliano Pet-Nat 2016 ($28)

A whole-cluster pressed, spontaneously fermented, methode ancestrale treatment of the classic northeastern Italian grape. Delicately aromatic, with vibrant acidity, brimming with bright flavors of white flowers, sweet almond, and green apple, and a suggestion of salinity -- fitting its origins. At just 9.5% ABV this would be a dangerously delicious addition to anything from charcuterie board to your New Year’s Eve celebrations.

For more on Long Island wine, check out the following Grape Collective interviews:

Joseph T. Macari Jr. and Gabriella Macari of Macari Vineyards

Miguel Martin of Palmer Vineyards

Kareem Massoud of Paumanok Vineyards

David Page and Barbara Shinn of Shinn Estate Vineyards

Special thanks to the New York Wine & Grape Foundation for graciously providing the author with the opportunity to learn first-hand from the producers mentioned in this article.

1. Quote by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie