Robert Parker was in Manhattan recently for the unveiling of the Wine Advocate’s newly redesigned website and he talked about Olympic swimming trials, why some wines began tasting alike on his watch and, among other things, one regret involving his mother.

He married his high school sweetheart, Patricia. He parlayed a love of wine, discovered in France with said girlfriend, into a career of public service, if you will, achieving international fame as the world’s most influential wine critic. Samuel Dash, the great chief counsel of the Senate Watergate Committee, taught him a conflicts-of-interests course in law school. But there is something that Parker set his sights on and failed to achieve.

“One of my long-time objectives before my mother passed away was to get her high on wine, but she was so stoic and difficult that I never really achieved that,” Parker told a room full of writers who laughed along with him. Parker’s parents were dairy farmers before his dad went into heavy construction equipment sales. “My father just wouldn’t do wine at all,” Parker added. “He was a Kentucky bourbon guy.

“I came from that background and somehow fell in love with wine,” he continued. “I fell in love with wine. Fell in love with the culture of wine, the history of wine, the diversity of wine, and I think the great thing that I’m most thankful for in these 38 years is that my love of wine has never failed me. That’s the one thing that I hope I can pass on through the Wine Advocate.”

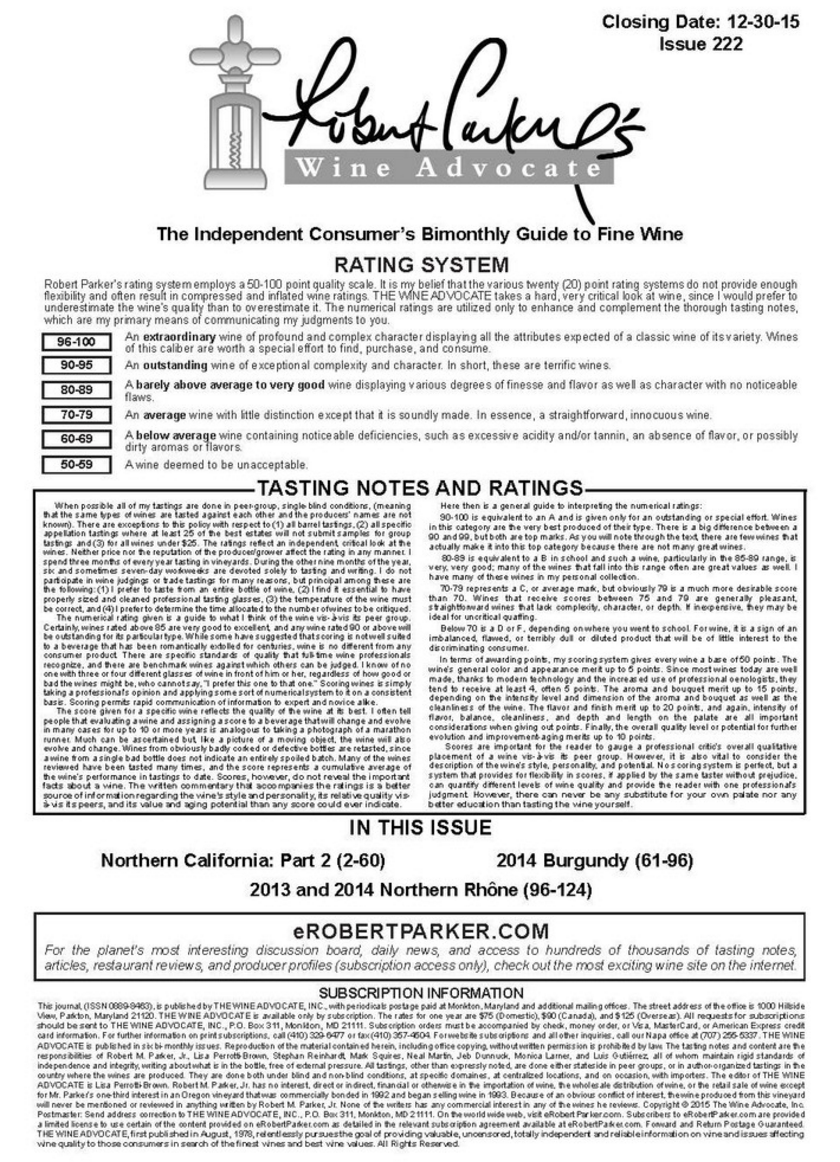

Robert M. Parker Jr., now 68, is still doing his best to pass on that love. It has been 38 years since he founded the Wine Advocate, a newsletter of tasting notes and numerical scores that is the equivalent of the gospel in the wine world. A score of 100, the Holy Grail. Three years ago, Parker sold the majority interest in the Advocate to people he described as “some young wine lovers in Singapore.” The first WA issue had reviews of 300 wines, the most recent more than 6,000, he said, adding that in 38 years it has never received “one cent from advertising, it’s independent, and never had one score leaked.”

He was in New York at the Mandarin Oriental hotel with the entire globe-trotting WA reviewing team along with Lisa Perrotti-Brown, MW, who is editor-in-chief of The Wine Advocate & eRobertParker.com. Even Liwen Hao, the newest team member was there. In addition to several days of wining and dining with winemakers, and master classes like “Harlan Estate, California’s ‘First Growth,’” the event gave the New York press a sneak peek at the newly expanded and redesigned website, that will be available to subscribers onApril 1.

Looking like a well-aged mash-up of Michael C. Hall and Matt Damon with a dash of Neil Young for hip boomer cred, Parker almost levitated with joy discussing improvements in the quality, diversity, availability and affordability of wines today. And he was even-tempered and firm in his defense of his controversial 100-point rating system.

“People say, ‘Well, the point system is a simplistic system and it’s very subjective.’ Well, sure. I can say that when I’m watching Olympic swimming trials or ice-skating or whatever. But I think with the scoring for me of wine, it is important that every score have a very intelligent tasting note attached to it. We couldn’t have one without the other.

“The idea is that, sure, you can write a good tasting note. But the score is your stake in the ground. It’s the stake that you throw in the ground. You say, ‘I am accountable. I am accountable because I gave this a 92 or even a 97 or I gave it a 75.

“Maybe it’s come from that conflict-of-interests law course I had in law school, or it comes from being influenced by Ralph Nader in the ’60s. But I think it’s important a wine critic be accountable for everything they write and the score is one way that they can be very accountable and it’s shorthand.”

When John and I wrote “Tastings,” The Wall Street Journal’s wine column, we borrowed the wine rating system we had used in our private life for more than two decades. It went Yech, OK, Good, Very Good, Delicious and Delicious! We knew what we meant and figured other people would, too. But we always, always, counseled people to discover what they liked and told them no one could tell them what a wine tasted like to them. If they found that we had similar tastes and they therefore could trust us to be a guide, great, but it was always about their journey.

Parker’s system is called the “real world system” because it’s the way most high schools in the U.S. grade students. Years ago, Jancis Robinson’s website had an interesting graph that broke down the various rating systems, including ours. Here’s what it said:

“Robert Parker/Wine Spectator—The 100 point system was introduced by Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate in 1978.Very much like its real world model, 60 or above is acceptable in theory but in reality a rating under 80 can make a wine unsellable. As imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, the Wine Spectator adopted Parker’s system and helped make the 100 point system huge.”

Critics, as in the movie Mondovino, assail what they say is the globalization of a style of wine that is pleasing to Parker and jet-setting consultants like Michel Rolland. They argue that winemakers all around the world make wines tailored to Parker’s taste and hire as consultants people whose wines he likes, like Rolland, so that he’ll give them high scores that stores and restaurants then use to sell the wines. In this scenario, the uniqueness of wine regions worldwide, their particular terroir, is sacrificed for money and fame.

Even winemakers who admire him a great deal concede some of that happened. Paul Hobbs, the famous Malbec whisperer, told me last year that Parker was “the most influential critic of all time, the world has ever known,” adding, “I don’t think it’ll ever happen again.” Hobbs was not talking narrowly about Parker as a wine critic but a critic “of any type of subject matter.”

Hobbs said, “With that kind of power is the ability to influence buyers, and buyers with money. If you’ve got a big score, wineries begin to chase scores, because that meant you put your wines in the hands of where you wanted your wines and you could charge more. Every winery wants to optimize their profit, as does anyone in business. That led to, I think, a misunderstanding, and I don’t think that was ever intended. It was a disservice to Mr. Parker’s work.”

“I found him to be not interested in over-extracted wines as much as I think people talk,” Hobbs continued. “He was more balanced.”

Before his public comments, I spoke with Parker. “I think it’s human nature that when you have very successful people, people who are very prominent in their fields of endeavor, that there are people who observe them, and I think it’s sort of natural. I do the same thing. They try to study their tastes and they tend to simplify, compartmentalize and pigeon-hole people, particularly with something as subjective as tastes,” he told me.

“Parker likes wines that are big and powerful,” he told me, repeating what “they” say. “There have certainly been some wines like that that I’ve given terrific reviews to, but I like delicate wines, too. To me it’s not a question of power but one of balance and personality. I like people to have personality. They’re interesting to talk to. I like wines that say something back to me, that hold my interest like carrying on a conversation with someone. So I think Paul was right about that.”

“Certainly high scores and favorable reviews create success and create interest in a wine, a brand, whatever,” Parker told the gathering. “I think that my 38 years have been parallel to an incredible uplifting of quality as well as diversity of styles. I think you see this everywhere. Now one of the things that also happened during those 38 years that I don’t think existed before that was that you had the development and the growth and the hiring of the super consultants that went around the world.”

This development, he said, started with the late Émile Peynaud, a French oenologist and scientist at the University of Bordeaux, who has been called “the forefather of modern oenology.” Peynaud preached later harvests, better sanitation, making wines that reflect their origin and type, Parker said, but when Peynaud gave that advice to some wine regions in the 1950s and ’60s they couldn’t afford to act on it because of their struggling economies. As their financial pictures brightened in the 1980s, they began to make improvements and some flaws disappeared from their wines, Parker said.

Peynaud influenced many other oenologists, like Rolland, who Parker called Peynaud’s most famous student who has around 200 clients worldwide. Parker said he is one of the few critics who has tasted all of the Rolland-assisted wines. “He does have this philosophy of making wine; there are similarities,” Parker said. “He says, ‘You should only pick mature fruit. I don’t want you to be picking under-ripe fruit. I don’t want you to be picking over-ripe fruit.’” But ultimately, Parker said, “he wants the wine, whether it’s from Chile or from Spain, to represent its place of origin.”

Parker does make this concession: “This is one area where I think there has been compromising. I think because of all these interactions with consultants, because of this general philosophy of picking later and better sanitation, better cleanliness, there has been sort of a blending and a blurring of some of these geographical differences. I think this has actually kind of increased quality, that you don’t see the flaws. ”

“When I started tasting you could probably count on 10 per cent of the wines that we were going to open were spoiled. They had volatile acidity, they had excessive sulfur,” he said. “Today that almost never happens because winemaking has gotten so much better.”

Part of “the learning curve,” he explained, is that “the areas that were behind in technology, behind in expertise, catching up they may have tried to make wines like somebody else, but I think that’s just all part of the educational process.”

Still, he vehemently rejected the notion that winemakers try to please him and his team. “I don’t know any respected winemaker, wine producer, that we’ve given high reviews, that wanted to make a wine to please any of us. That is selling your soul out big time. It just goes against everything that you would compromise your own principles, your own love of wine to make something for some wine critic that may only be there five years or 10 years. I’m the exception. I’ve been around for 38 years.”

He has other worries. “There’s no question that we have this centralization not only of wine distribution, where small, boutique importers and distributors are being bought out by the big giants, but we’re seeing it in the small vineyards,” he said.

Parker recounted a recent visit with Tom Rochioli of Rochioli Vineyards and Winery in the Russian River Valley who lamented to him as he had to me that he was already involved in succession planning because so many family-owned wineries had been sold to large corporations. Parker hastened to say that just because a winery or chateau is owned by a large corporation doesn’t mean its wines will be bad. Take, for instance, he said, French company AXA. It’s one of the largest insurance companies in the world and has a wine division, managed by Christian Seely, that owns some of the most impressive vineyards in the world.

“Right now, there’s no question. I see it especially in California that big companies are making big moves. The Gallos are buying a lot. Kendall- Jackson is buying a lot. It’s tempting [to sell] because they have a lot of money, and land, vineyards, they’re not making any more of.”

For his part, Parker said he is just telling readers what he likes. When he was starting out, he said, “I was exposed to the British school of wine writing,” and he mentions Hugh Johnson and some others, saying, “They made incredible contributions to the literature of wine.” But, he adds, “They all hedged their bets when it came to actually evaluating wine. I could never really tell if they really liked something or if it’s just famous. The Wine Advocate, in a way, was an anti-reaction to that -- a reaction to that. You need to be held accountable. You need to take a stand. Hopefully, people will listen to you.”

“I’m very happy where I am. I hope I can keep doing it because if you’re a young up-and-coming wine critic, it’s one of the greatest and most exciting times to be around,” he said. “But you have to worry about too much corporate ownership, too much homogenization -- and it’s not really the Parkerization you need to worry about. I think if all wines became Parkerized, they’d be much better quality.”

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal.