In Goethe’s Faust, young Gretchen confronts the protagonist with an unsparing question (Frage). Gretchenfrage has come to mean an inquiry that pierces the heart of a difficult matter. Bellwether Wine Cellar’s Kris Matthewson relentlessly confronts himself with the Gretchenfrage of how to make wine in the Finger Lakes of New York worthy of the German masters he reveres. The subject obsesses Matthewson and for this, Riesling lovers should rejoice.

Few winemakers have read, thought, or trialed ideas and techniques in growing and making Riesling as intensively as Matthewson. He is just 36, but an early start, European-focussed training, and a relentless pursuit of the highest ideals for Finger Lakes wines seems to have packed each of his winemaking years with the density of decades. Talking with Matthewson for a few hours feels equivalent to a few semesters of study at Geisenheim or Cornell.

Few winemakers have read, thought, or trialed ideas and techniques in growing and making Riesling as intensively as Matthewson. He is just 36, but an early start, European-focussed training, and a relentless pursuit of the highest ideals for Finger Lakes wines seems to have packed each of his winemaking years with the density of decades. Talking with Matthewson for a few hours feels equivalent to a few semesters of study at Geisenheim or Cornell.

(Photo, left: Kris Matthewson of Bellwether Wine Cellars)

Yet, on Matthewson’s journey from apprentice to master, he has, by his own admission, had ambitions that outdid him, ideas that failed him, and ideals that isolated him. “The wine should be made in my mind,” he says. But the gaps between theory and practice, between the “conceptual” wines Matthewson makes and “normal Riesling drinkers” — to use his words — have not been easy to close. “I feel like I’ve finally matured to a point where I'm pretty happy with the way I'm using some of the ideas I’ve learned. Really taking what I've done in the past and what other producers have done, learning from that, and trying to implement it, but still having my own personal ideas. Terroir is one aspect of wine, but also the person. The idea of a cellar master in Germany, something we don't really have here, that's more of how I have always thought of myself,” Matthewson explains.

Unlike most Finger Lakes winemakers, Matthewson was born and raised in the heart of the region, in the village of Hammondsport, and got his first winemaking job at 19. This gives him a long view on developments here, as well as a close understanding of the lakes’ specific topographies, soils, and microclimates. He’s had nearly two decades to evaluate varieties, techniques, the wines of other producers, and to puzzle out which fit best with his own mindset. From this vantage point, he looks ahead to the near future in the Finger Lakes when we may see a gradual move to sites with thinner, less fertile topsoils, denser planting, more handwork — and in this, the increased possibility of organic and biodynamic viticulture, as more frequent and careful pickings allow for rigorous sorting rather than spraying.

Matthewson recognizes that was fortunate to be singled out for excellent training early in his career. He got his start at Bully Hill Vineyards, one of the true originals in Finger Lakes wine — notably, also the launchpad for Finger Lakes’ Riesling pioneer Hermann J. Wiemer, whom Matthewson unreservedly admires. While sweet, simple wines were the Finger Lakes’ stock in trade as Matthewson was coming up, he had the good fortune to be exposed regularly to cellared Rieslings from top German producers working across the spectrum of styles and regions. He also had the luck to be trained by winemakers from Europe or with European models foremost in mind. These shaped his palate and thinking in a very specific direction.

And yet Matthewson has never worked in Germany (he had a chance back when he worked for Bully Hill, but passed that up, a decision he says he now regrets) nor does he speak German (something he says he aims to work on). Having his head in Germany and his feet in the Finger Lakes pulls him in two directions. He wants to make wines that specifically reflect Finger Lakes terroir and could come from nowhere else: Riesling and a small amount of Pinot Noir from specific vineyard sites, using spontaneous fermentations, ambient cellar temperatures, extended lees time, and longer bottle aging to allow true site and style expression. But he also wants the wines to rise to the level of quality Germany excels in. For Matthewson, it all comes down to texture and weight: these are the elements he believes are still missing from most Finger Lakes Rieslings — and the ones he is most intent on nailing.

He believes lees times and bottle aging have key roles to play in this, as well as botrytis inclusion, but that the main actor may be none other than SO2. His embrace of added sulfur is controversial in our present cultural moment, but is entirely born of Matthewson’s respect for the texture and aromatics of German Rieslings and years of trial and observation. Matthewson works with an analog press built before the fall of the Berlin Wall — the same model the legendary J.B. Becker has — and insists on running press cycles based on the sound and smell of the press, not the beep of a digital program.

He is bothered by frequent comparisons between the Finger Lakes and the Mosel: “I would never say Mosel, I'd say Rheingau” — for its gentler slopes, late-season heat spikes, and ripening patterns. Matthewson also sees rarely discussed commonalities between the marine-based subsoils of the Finger Lakes and places like Champagne and Chablis that produce lower pH wines. He believes these similarities can and should have direct bearing on the wine styles he aims for.

Matthewson is candid and generous with his thoughts and perspectives. In my three-hour discussion with him he offered a trove of detailed and deeply technical information. But the scope and breadth of Matthewson’s understanding of wine and winemaking is so extraordinary, it felt important to share the conversation (almost) in its entirety. So please, get comfortable, open a mind bending wine (may we suggest Bellwether’s 2016 Riesling “S” or 2017 Pinot Noir rosé for the full experience?), and learn along with us.

Valerie Kathawala: What got you into wine?

Kris Matthewson: I grew up in Hammondsport, which is right on Keuka Lake.  It's a pretty historic winemaking town that’s kind of been lost post-Prohibition. My family wasn't involved in wine at all. But right before I went to college, I decided I should learn a little bit. So I went to a winery called Bully Hill and worked in the tasting room. A couple days after I started, the winemaker asked me if I could help him move a barrel. From that point on, I was a cellar rat. That’s where I feel like I have real skill: working with juice, fruit, and those things.

It's a pretty historic winemaking town that’s kind of been lost post-Prohibition. My family wasn't involved in wine at all. But right before I went to college, I decided I should learn a little bit. So I went to a winery called Bully Hill and worked in the tasting room. A couple days after I started, the winemaker asked me if I could help him move a barrel. From that point on, I was a cellar rat. That’s where I feel like I have real skill: working with juice, fruit, and those things.

(Photo, above: Aerial view of the Finger Lakes)

I think the people who trained me saw that I had a decent nose and palate and that was something they could benefit from. They trained me very well because of that. I think you need to be able to see what you're doing in winemaking way ahead of when it actually happens. That is just experience. Now I always try to give it to a younger local person in my cellar because somebody gave me that chance and I want to pass it on. There's not a very large portion of people making wine who grew up in the Finger Lakes. Really, just me and Nate Kendall. And other than people whose families own wineries, there aren’t a lot of people who have that. So that is something that I really hold dear. I've been in that town my whole life and seen the wine, the region, the culture evolve.

But getting back to Bully Hill: We’d do tastings on Fridays, and we would have a lot of German wines, because there had been five winemakers from Germany who worked at Bully Hill.

Was Hermann Wiemer one of them?

Hermann was one of them, as well as a lot of the people that worked at Dr. Konstantin Frank, a lot of people that went on to that generation of wineries in the Finger Lakes. Everyone associates Bully Hill with fun, sweet wines that are a little more simple. I was tasting those and making those. But I was also being given top German estates to taste — traditional Auslese, Beerenauslese, Trockenbeerenauslese. Because back then you didn't really see as much trocken-level wine in the U.S. These were wines from the mid-‘90s that had had ten years in cellar, so they were really amazing. Some of the producers I really love in Germany now are still the producers I got to taste then: in the Pfalz, Dr. Bürklin-Wolf, and in the Mosel, Heymann-Lowenstein, which is my absolute favorite German producer.

I stayed at Bully Hill for four years and I really got into it. It wasn't like I was trying. I was playing soccer in college and coaching, and I thought I was going to do that. At the end of college, I had been offered the associate winemaker job at Bully Hill. Part of that is they would've sent me to Germany for a year to train and work, which I regret not taking. The other option I was offered was a soccer coaching position at a college. I turned both down and went back home.

After that, I worked at a couple wineries, in distribution and at wine shops. I realized I loved doing it and was good at it. I went to another winery, Heron Hill, and the same thing happened. At the time, Heron Hill had a Hungarian winemaker named Thomas Laszlo. He had worked in Bordeaux at a premier cru and been the winemaker at the Royal Tokaji Company before that. We were making very good wines, but his ambition was greater.

A lot of the techniques I learned for making dry wine were based on what he taught me: fermentation techniques, allowing more lees time, the idea that maybe reduction isn't a horrible thing. And that we should be pushing for quality German wines, not just wines that consumers will sop up.

Why Riesling?

I always had this Riesling thread going through everything because I grew up in the Finger Lakes and I’ve watched Riesling become more and more popular, and what was going on in Germany, the more modern styles in Germany, more aligned with what I was thinking of for Riesling.

Just to be clear, your knowledge of German producers and wines is all from books and tastings?

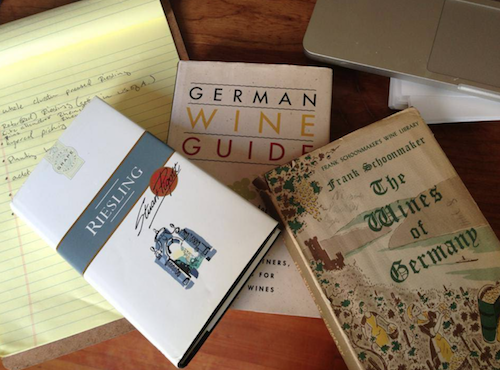

Yeah, it's all theoretical. I've been tasting German wines for 17 years now.  And I read every possible thing that I can, and when you're making wines as well, you can try the little things they say to do. I love reading the Schoonmaker book [Wines of Germany, 1956] and I pick up things. Just one sentence can change the way that I think about how I’m making my wine. I don't think that someone who’s not a winemaker would pick up on what they're saying.

And I read every possible thing that I can, and when you're making wines as well, you can try the little things they say to do. I love reading the Schoonmaker book [Wines of Germany, 1956] and I pick up things. Just one sentence can change the way that I think about how I’m making my wine. I don't think that someone who’s not a winemaker would pick up on what they're saying.

(Photo, left: A sampling of Matthewson's wine studies)

The Finger Lakes is a Riesling culture, although I think it's evolving a little bit away from that. But during the time that I was coming up, Riesling was going to be the way we made the Finger Lakes stand out. There were tastings, people being brought in to discuss it. Cornell was doing a lot of research. What I noticed was a lack of desire to learn from German wines, which didn't make sense to me. Nobody was even paying attention to the Terry Theise or Rudi Wiest import books.

In Germany, there's an evolution every year. I've paid a lot of attention to that, and I think that's allowed me to be more on top of my game. But it’s also really a detriment because I'm chasing styles that are popular in Germany a year prior and developing my own thing — a style that’s lower in aromatics, more textural, more linear, with more acid, more mid-palate weight, and more fullness from more lees work — that really came from reading about German producers who were doing these longer lees contact dry Riesling that were not quite GG level, but right below GGs. I wanted to do that. And there's no way in hell a Finger Lakes producer was gonna let me do that. So I had to do it myself.

It’s about single sites and single techniques in Germany. Dr. Loosen’s wines, some are single site, but it’s the aging, the extended aging. Heymann-Lowenstein wines are very site specific, but they're also very cellar specific in the way that they're dealing with their juice, clarity, and reduction. And that's one of the things that I love about those wines and the style of reduction that they get.

How do you see yourself as a winemaker?

There’s a thing I think people don't understand about my wines: People see me as someone who just jumped in, did all these crazy things, was one of the first to do pét-nats or all these uninoculated, unfiltered wines.  Well, those were really ways of me experimenting with a technique or an idea so I could take that further into my winemaking. I’ve fermented hundreds or thousands of different lots of wine at this point. Still, I'm always terrified with my first picking of the year that I forgot, that I'm not going to be able to ride the bike again. But by the second picking, I'm always like, okay, this is fine.

Well, those were really ways of me experimenting with a technique or an idea so I could take that further into my winemaking. I’ve fermented hundreds or thousands of different lots of wine at this point. Still, I'm always terrified with my first picking of the year that I forgot, that I'm not going to be able to ride the bike again. But by the second picking, I'm always like, okay, this is fine.

(Photo, right: The winemaker at work)

I try to use the techniques that someone of my grandfather’s generation, not my father’s, would have used. And I think that's what you see in the German wine culture, too. In the past, the German wines that were dry would be left in the cellar for years, so there was no possibility of problems in the bottle. So those older books, anything a German wrote about German wines pre-1990s, are really what I focus on.

Any specific resources?

You can read a lot of this stuff through Lars Carlberg. What he's doing is a huge resource for me. Stuart Pigott, in a lot of his older writings, has things on Germany I really like. Frank Schoonmaker. So, I'm reading every possible thing I can. I also take ideas from Champagne production, Chablis production. I think those are applicable to what I'm trying to do with dry Rieslings. I'm really obsessed with it to be honest.

The problem with me is I think I out-think myself sometimes. I definitely have out-thought myself. I was being way too ambitious with technical things in the winery, in the vineyard, with pickings and everything. And then I’ve gone back, and I really enjoy these wines, and I think people who are into German wines are going to enjoy these wines. But I don't think they have a broad appeal for normal Riesling drinkers. They were more conceptual I think.

Now I feel like I finally matured to a point where I'm pretty happy with the way that I'm still using some of those ideas. Really taking what I've done in the past and what other producers have done, and learning from that, and trying to implement those ideas, but still having my own personal ideas. Terroir is one aspect of it, but also the person. The idea of a cellar master in Germany, something we don't really have here, that's more how I have always thought of myself.

But I really just keep to myself. Honestly, I just like to buy a bottle and focus on it by myself. Cook dinner or just have a bottle. I also like to taste bottles over days to see how they evolve. It's gotten to a point where drinking wine is an intellectual exercise, which is a little draining of the pleasure, but every bottle of wine I taste, I try to figure out what’s in there, scour the Internet for any notes I can find or philosophies of the winery and things like that, or contact the winemaker and trying to figure out what is there that I can use myself. I was listening to this thing about Bob Dylan, how he stole all of his friends' records. He told his friends, ‘You don't need these, they benefit me more than they will you.’ I feel like I kind of can understand that statement. Which is, I know, is a horrible thing.

What distinguishes German Rieslings from those of the Finger Lakes?

When Bellwether started, I had all these ideas about how I wanted to change the way we were making Pinot Noir and Riesling.  Going for more of an austere, dry, mineral style with textural components. When you talk to German winemakers, they talk about acidity, sugar, balance — and texture. Texture and weight were the components that I felt were going to push us to the next level in the Finger Lakes.

Going for more of an austere, dry, mineral style with textural components. When you talk to German winemakers, they talk about acidity, sugar, balance — and texture. Texture and weight were the components that I felt were going to push us to the next level in the Finger Lakes.

(Photo, left: Hand-picked Riesling grapes)

How did you set about making “German” Rieslings in the Finger Lakes?

I started examining ways other wineries were doing things. But I didn't want to do it with a bag of powder that I bought from a company. Because in my mind, throughout history, great wines, Rieslings in particular, were made with sulfur basically being the only tool. So there have to be ways we can make Rieslings that have that textural component, ways we can balance the wine through physical processes. Forethought, really.

There should be forethought about what you want that Riesling to finish as already when you're in the vineyard — when you're picking and the way you're dealing with your fruit on the press pad, those physical ways of extracting texture, aromatics, and ripeness. Work in the cellar should just be about getting there.

The other thing is: there's a timeframe within which traditional Finger Lakes Rieslings are made. You pick in the fall, of course, and then you want the wines off the lees within a week post-primary fermentation. Some of what I was reading was saying to do the same, but even in Germany, even the producers that are bottling early, they're not taking the wine off the lees that early. They're typically leaving it on the lees and then maybe they're doing different types of filtration right before bottling.

Cross flow filtration is extremely popular in Germany. It’s a different technology that allows you to use only one pass at filtration, with less intervention and less oxygen pickup. You’re going to want those wines to market by spring. And some of the German producers I was looking at, yeah, some of them are to market by spring, mid-summer. But that's never their top wines. Their top wines are always to market the following year.

Does SO2 play a role in this?

For me, the way German producers manage sulfur is a major component in German dry and off-dry Rieslings. Because in terms of requirements for stability and bacterial issues, sulfur's way overused there. So there must be a secondary component they're using the sulfur for. The way you're using sulfur should be an idea expressed in the overall idea of what you're trying to get in the finished wine. So I started playing around with less sulfur. Trying to see how little sulfur I actually needed.

What did you conclude?

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this. Sulfur is related to salt in its molecular makeup. When you think about German wines, or Austrian wines, or my wines, typically there are periods of extended time on the skins, or press cycles, or macerations, and you have high tannin content. There’s the possibility of picking up bitter notes from those extractions, whether from the pressing or maceration. So, just as when you add salt to bitter coffee, you get rid of some of that bitterness, you can mask some of those bitter components and get more extraction through the use of sulfur.

If you look at the Finger Lakes, Germany, Austria, even Chablis, they all have hard sub-soils that are fossilized marine-based. There's this strong common theme that every region whose wines I love, they all have that, and they're all, in general, Devonian sub-soils. That and the next epoch are the two time periods when those sub-soils developed, essentially. And all those areas were seabeds at that point. When you think about all those sub-soils, they're all going to produce wines with lower pHs, because they're harder and there's less nutrient availability. So you'll have the likelihood of getting more reduction because you'll have lower pHs and you're going to be more likely to have higher hydrogens. So you actually have more likelihood of picking up sulfur-based aromatics.

Could you back up there a second?

Sorry, I know this is crazy. These sorts of soils have low nutrients because they have high hydrogen and lower pHs. This makes the wines more susceptible to developing reductive characteristics with ambient fermentations without intervention of nitrogen. So there’s more capacity for reduction in fermentation if you don't balance out the nutritional needs of the yeast.

So one of my ideas was, the second we bring in the fruit, we unbalance the juice by adding commercial yeasts.  So we're always going to have huge reduction issues in the wines because of the biology of the yeast that we're bringing in. The idea is that the yeast that's involved in our vineyard sites or other bacteria should naturally be balanced. As soon as we take out that balance, we'll cause issues and reduction could be one of those issues. So as soon as you add a commercial yeast, you have to add the nutrients that commercial yeast requires because the environment doesn't have the capacity to fill those nutrient requirements for the yeast. But if we don't mess with it, it doesn't need to be readjusted.

So we're always going to have huge reduction issues in the wines because of the biology of the yeast that we're bringing in. The idea is that the yeast that's involved in our vineyard sites or other bacteria should naturally be balanced. As soon as we take out that balance, we'll cause issues and reduction could be one of those issues. So as soon as you add a commercial yeast, you have to add the nutrients that commercial yeast requires because the environment doesn't have the capacity to fill those nutrient requirements for the yeast. But if we don't mess with it, it doesn't need to be readjusted.

(Photo, right: Behind the scenes at Bellwether)

Current research says 80% of ambient yeasts come from the vineyard and 20% from the cellar. So, your house as well as the vineyard plays a part in what yeast you're using, which I think is really cool because it shows that the vineyard can carry through, and that your house style plays an important role, too.

The other thing is there are two ways of doing it. The primary way is to pre-select the indigenous yeast by bringing in the grapes, getting a starter going with that, and then doing a pied du cuvée [a traditional yeast starter, similar to letting flour and water absorb ambient yeast to start bread fermentation, then taking some of that starter and using it to kick off fermentation in other batches of dough] maneuver from tank to tank. Or adding starter from the vineyard into the tank.

But the way I do it is I just let the tank go. Because pre-selecting is still selecting and then if you want the site to really speak, essentially, it can’t.

That being said, do you ever use commercial yeast?

I only used commercial yeast once, in 2012, the first year I did Riesling. I also did the same Riesling without commercial yeast, so I could learn how to work in that way. And from that point on I haven't used commercial yeast.

With the Rieslings where you just let the tank go, do you let the fermentation stop where nature says, or do you have an idea about that beforehand?

It depends. The cool thing with Riesling is that it has balance points. The wine can change depending on the balance you're going for. In general, I try to pick the wines that I want to be dry by a certain point. And I use cooling to stop the fermentation.

Can you explain the role of cellar temperatures in Finger Lakes Rieslings?

The biggest asset I think we have in the Finger Lakes is that our cellars can slow and stop fermentations. People always come to my cellar in the winter and complain that it's cold because we’re tasting together and it’s taking kind of a long time because I have all these pickings and sites and tanks to work through. It's maybe 37F, 40F in the cellar. That stops the fermentation. So typically the wines that I want to have more sugar are picked later because I want them to have more ripeness and complexity, or if I want the ones that have more sugar in the beginning then I'll just have a lower fermentation temperature to start.

In general in the Finger Lakes, Rieslings are fermented between 58F and 65F. But now you're seeing more modern producers of dry Rieslings fermenting at higher temperatures and sweeter wines at lower temperatures. My dry Rieslings, I'll just let them go, and if the wines come in at a certain point in the fall when it's starting to get cold, then I'll just let those wines use the ambient temperature of the cellar. I'll also move tanks outside at night because we have huge diurnals. Once you get to October or November in the Finger Lakes, you might have a 60-degree temperature swing. A couple of years ago, I made some Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA). The day that we picked it was 60F and the next day it was 15F.

Speaking of TBAs, how do you deal with botrytis?

Traditionally there was no botrytis sorting in the Finger Lakes. Just because we didn't have the manpower to do it — we still don't. I've done it a couple of times.  Probably Wiemer and myself are the only people who are isolating botrytis. And the TBA I made, that's literally individual berries. I selected for berries, which is extremely rare. Most people will do cluster selections.

Probably Wiemer and myself are the only people who are isolating botrytis. And the TBA I made, that's literally individual berries. I selected for berries, which is extremely rare. Most people will do cluster selections.

(Photo, left: Grapes affected by botrytis)

Most of my wines will have botrytis. And the level of botrytis will determine how long my press cycle will be. If my fruit's clean, the press cycles will be longer, but if there's botrytis, the press cycles will be shorter. And that's just from reading about Austrians and Germans not wanting long press cycles on botrytis. I don't even know the rationale for it, to be honest. Probably dehydration of stems and then extractions of tannins and skins, essentially.

Broadly speaking, what are the key similarities and differences between the terroir of the Finger Lakes and Germany?

For me, the big problem with the Finger Lakes is that we're not, as everyone says, like Germany. The key difference is we do not have a long growing season. We have a late — hopefully late — bud break because we don't want frost, we don't want any cold coming in and killing, which has happened quite a few times recently. Also, our ripening really accelerates at the end. We come into September almost unripe. And within the first two to three weeks of September, all of our finishing occurs. And we'll go from grapes that are unacceptable to pick to 23 Brix with 3 pHs.

Historically in the Finger Lakes, picking at a pH of 3 with a total acidity of 8 or 9 grams per liter and 21 Brix was the thing we were all searching for. I try to look at the pH and Brix. But we really have this ripening acceleration at the end of the growing season and we can lose acid quickly. In the last week of August, the first week of September, we'll get days that are 100F, almost given. We'll have a stretch where it's 90F for a solid few days. And that's when we finish our ripening, because we have this late heat. So for me, if I had to compare, I would never say the comparison is the Mosel, I'd say Rheingau. Some of the producers I love best are from the Rheingau — Carl Ehrhard, J.B. Becker, Leitz.

And in the cellar?

I have an old German press, a refurbished Willmes 1500, which is the press Becker and Leitz have. I think Falkenstein uses that press as well. Mine was completely rebuilt in the Mosel and then repurchased here. I'm always near the press and always want to be controlling the way I'm extracting. Most presses are digital now. You type in a program. But because this press is analog, you have to be completely involved with what you're doing. I think that's super important.  A lot of it's aromatic and auditory when I'm doing the extractions because I've been working with the same style of press since 2009 or 2010. I’ve spent all that time learning what the pomace needs to sound like and what the juice needs to taste like, and what the clarity needs to be. I can be across the winery and know by the rate of drip or the aromatics.”

A lot of it's aromatic and auditory when I'm doing the extractions because I've been working with the same style of press since 2009 or 2010. I’ve spent all that time learning what the pomace needs to sound like and what the juice needs to taste like, and what the clarity needs to be. I can be across the winery and know by the rate of drip or the aromatics.”

(Photo, left: Matthewson pressing grapes with his WIlmes 1500)

For me, the pressing is the final part where I'm gaining or taking away anything. So the press pad work is super important. Most times I use extremely low pressure press cycles, with half a bar. I typically do three press cycles per 500 gallons. There are three ideas of extraction throughout each one of those. So one's a quick extraction. A 45-minute press cycle.

I'm giving away all my secrets.

Please do.

Anyway, all my single site Rieslings, there's one press cycle like that. The second press cycle is typically from four to six hours with a lot less rotating of the press, so I'm not breaking up the cake. And giving the pressure and then letting it bleed out, essentially. And then the final style of press cycle is pressed lightly. And then given up to about one bar, and then left for about 12 hours to drain. And then all those pressings go into one tank, though they have been separated.

Are you using different proportions of the pressings?

No, they're all even.

So you did that just to learn, and now, what's the rationale for separating them out like that?

Well, they're together now, but the rationale to separate them out was to see what happened texturally. The middle pressing is probably what I would do if I were to do just one style. And this all changes depending on the extraction and the amount of botrytis and the bitter components.

Let’s talk about viticultural challenges to working in the Finger Lakes. Is there one that looms larger than all the rest?

Climate. We have every imaginable problem. And we have low labor availability for vineyard work compared to other regions. I look at other regions, and I'm like, God, it would be so easy to make those wines. But on the flip side, we have acidity that everyone else would kill for, which gives us stability in our wines. And our grape costs might be high, but our land costs are still very low. And that's what's concerning for me as someone who's growing: right now is the time I need to buy vineyards.

You tried to get one that was very important to you, right?

Yeah, I tried to get A&D. But that didn't work out, and it's just gone now.

And there are a lot of vineyards like that. Keuka Lake in particular has a lot of vineyards that are being abandoned because it's more en vogue to be growing on Seneca Lake. The funny thing for me is the reason there's growth on Seneca Lake is because when the people who are moving to Seneca Lake were establishing their vineyards, it was because land was cheaper because all the vineyards were on Keuka Lake then.

What about individual sites?

If you drive around the Finger Lakes, there's typically a lower lake road, a middle lake road, and a road on top of the hills. And each of those roads is where the grade breaks in the soil.  So those roads were put there because that's where there was a change. So for me, you want to be on one side of the middle roads. On Seneca Lake, there's more on the non-lake side of those roads than on Keuka Lake. And if you look on Keuka Lake, too, you'll find more grade, and therefore less topsoil, and more exposure to subsoils, and that's something I think needs more exploring.

So those roads were put there because that's where there was a change. So for me, you want to be on one side of the middle roads. On Seneca Lake, there's more on the non-lake side of those roads than on Keuka Lake. And if you look on Keuka Lake, too, you'll find more grade, and therefore less topsoil, and more exposure to subsoils, and that's something I think needs more exploring.

(Photo, left: Vineyards overlooking the lake)

The reason the vineyards are located where they are is there's traditionally been a culture of machine work and harvesting, and that's why some vineyards are where they are. I think you're going to see the most growth in quality where the vineyards shift a little more north because you're going to see people working on more slopes with less topsoil and this is going to mimic more of what you see in German regions. That's another reason Rheingau makes a little more sense to me as a comparison, because the grade we have is similar to what they're working. They're gradual hills, not steep slopes. As you see more and more people wanting to do this for Rieslings, I think you'll see more people doing hand work in those sites, with more density in the plantings. I think, too, switching from trellis to single post is going to be something you'll see with Riesling in particular because there's no point in trellising those lower sites. And beyond that, you'll get airflow to prevent sour rot and botrytis. But I think it's going to take someone really investing.

What else do you see for the future of the Finger Lakes?

I feel like I'm going to be around for another 20 years, and the people that I came up with are not. They were there 10 to 20 years before me. And a lot of those people stepped out of winemaking or passed winemaking on to other people. But that's not an option for me at this point. I think what you've seen in the last five years in particular is very different than what you saw in the past. And I think the next five years will be even more different.

What worries me is that there's a lot of competition for Riesling and that consolidation is occurring right now with producers, and it might not be that they own the estate, but they've consolidated through brokers or solid contracts, and there's not going to be as much to go around. Plus, we have a ceiling that we've created for our Finger Lakes Rieslings. But German wines are not that expensive. If I'm gonna spend $35, I can get an amazing wine from Germany.

For me, I have this ideal winery in my head that I don't think I'll ever be able to get to because you'd have to have a large investment. I think a gravity flow built into one of these hills with single post trellising on slate exposure with higher grade slope would be the way I would move forward, and then multiple clone plantings. Instead of doing pickings doing pass-picking. In Germany, pass-pickings are selected pickings of certain passes. In the Finger Lakes, you would do a pass-picking where you pass and pick two rows, essentially. You can have great diversity that way.

I've picked Riesling that has just gone from green to green-gold, the specks. That was the picking requirement. And that's been done and the botrytis was picked out. I think Wiemer will really be the one to do this. That's also the way that you can get a push toward organics or biodynamics, by embracing that we're gonna get botrytis. Embracing that there's gonna be uneven ripening in the vineyard and just working with it instead of trying to fight it with sprays and things like that. But again, you need a larger budget than I currently have, and you need a lot of labor.

Which producers closer to home inspire you?

For me, Wiemer is the standard. Growing up, Wiemer was a demi-god. I think Wiemer is the best white wine producer in the United States. But, again, because they're in the Finger Lakes, they're undervalued. I don't think people understand how great they are. The wines are always precise and represent Wiemer.

Nate and myself are closer to Wiemer than other producers in the way we think about how we're making Riesling, though we're all completely different as well. Wiemer's wines are typically a little broader, more floral, with more fruit, a little deeper into ripening. Mine are usually more mineral, more textured at the back end, not as tanniny, and there's the warm plush polish at the back end. Nate's are somewhere in between.

I like what Hermann did a lot, and I think [current winemaker] Fred [Merwarth], just like myself, is best with German wines. They have more of a focus on the vineyard, and they have more financial ability to have so many people involved with it that they are able to do things a little differently than I can. Like their sorting in particular and the equipment they've invested in. Their vineyard manager has been an amazing step forward for them. I learned about using cross flows from Fred. So they've just done a lot of things well. Wiemer and Ravines have been really encouraging. With that said, there's I think there are about ten wineries that I personally take seriously in the whole region.

Would you like to say who they are?

I would not. [Laughs]

What advice would you give to newcomers?

I think that the hardest part for people is understanding there is an established vineyard and winemaking culture in this region. For the vineyard culture in particular you need to learn how to work in that framework and make subtle changes to it, and not come in and tell people you're doing it completely wrong, and this is how you do it. You have to understand that many of these people are doing this second, third, fourth generation. And they're doing things the way they are because that was the framework that they were presented with from the people purchasing the fruit.

And you just have to work with them slowly, and if you don't want to work with them, you have to buy property and make your own vineyard and do all the changes, and take those risks yourself. Because you're coming into it without experience in probably one of the hardest viticultural regions in the United States. If you don’t have capital and you don’t have experience, the way you go about combating that is to use every spray available and you crop. And cropping is done at a rate that was established when people were really being paid to push, and there weren’t acre contracts. It was like, how many tons can you get off that acre? So there is the cultural aspect to them doing that.

That’s such an important aspect to consider. You’ve given us so much food for thought. Before you go, could we talk for a minute about the 2017 Bellwether rosé you brought with you?

Sure, this is a Pinot Noir from Sawmill Creek on Seneca Lake in the Finger Lakes. To our point, it’s machine picked. This is the only machine picked fruit that we use just because we're picking right before there's any issues with the fruit. And then it'll be clean fruit that'll be at the right ripeness level. Then the wine is fermented spontaneously, sees about 10 hours on the skins, and then there is fining and filtration right before we bottle it. But no other adjustments.

The color's very different from the 2016.

Yeah, because this is the first year we used machine-picked fruit. Typically I get my fruit from Sawmill Creek in the afternoon. But they machine picked in the morning and then because it was crushed from the machine picking it basically had extraction all day. It’s not what I typically do for Pinot Noir, for rosé. I want it to be more like white wine and this is more like red wine. It has a lot of the characteristics of white wine, but it has a lot of the tannin and the type of fruit that you're getting from the wine is more associated with red.

So this wine is also fined because of that. Typically I don't fine. But because of the extraction and also when you talk about contact or skin contact or extraction, you have to talk about the ambient temperature of the juice. So the day that this was being extracted it was warm, so it even pushed back the extraction more. So the color is a lot deeper, denser than normal. I was like, okay, this is still rosé, it's just not typical. I think there is this move toward a little bit more extraction in rosés. But maybe that's me rationalizing it.

It’s fitting that Jon Bonné recently tapped Matthewson’s rosé as one of his top picks for 2017, saying, “This showcases what pinot rosé does best: provide a subtlety and fragrance worthy of the grape, while still delivering zingy, tart pomegranate and apricot fruit. It’s about as cerebral a rosé as anyone wants in summer.” And that should get you thinking.

For more on wine from the Finger Lakes, check out:

Valerie Kathawala's article What's Behind the Stunning Rise of Finger Lakes Wines?

Valerie Kathawala's article on Nathan Kendall

Our interview with Christopher Bates of Element Winery

Our interview with Fred Frank and Meaghan Frank of Dr. Konstantin Frank Wine Cellars

Our interview with Kelby James Russell of Red Newt Cellars

Our interview with Fred Merwarth of Hermann J. Wiemer Vineyard

Our interview with Tom Higgins of Heart & Hands Wine Company

Our interview with Morten and Lisa Hallgren of Ravines Wine Cellars

Our interview with Shannon Brock of Silver Thread Vineyards

Our interview with John Martini of Anthony Road Winery

Our interview with Kim Engle of Bloomer Creek

Our interview with Nancy Irelan of Red Tail Ridge